People in Place

- Early modern London

- Family and household

- Marriage and family formation

- Births, baptisms and foundlings

- Apprenticeship and service

- Housing and accommodation

- Environment and health

- Conclusion

Early modern London

Between the early sixteenth and early eighteenth centuries, London evolved from a compact, coherent city into a sprawling and heterogeneous metropolis, the largest in Europe. Its population grew from around 80,000 inhabitants in the mid-sixteenth century to well over half a million by the end of the seventeenth. By 1700 it contained nearly 10 per cent of England's population and much more than 10 per cent of the nation's wealth.

London exercised an enormous influence in national politics and in the country's economic development, as it became the capital of a centralising and increasing powerful government and the entrepot of a new global trade network. It was a social and cultural capital too, a redistribution centre for material and cultural goods, and for a mobile population marked by the practices of the metropolis. Immigration, urbanisation, and commercialisation fostered new patterns of sociability, gender relations, employment, and consumption.

London's rapid population growth was largely due to migration, since the capital's unhealthy environment reduced or stalled natural population increase. Migrants came mostly from the English provinces, and from Wales, Scotland and Ireland; substantial numbers also came from embattled Protestant communities in France and the Low Countries. A significant Jewish community developed after 1650, and people of African, Asian and occasionally American origin were also to be found in London.

As London grew and spread in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, it became more clearly differentiated from area to area. While social and economic values had always varied from centre to periphery, a wider range of topographical variation developed, both in the kind and quality of housing and in the people who inhabited it. The research project 'People in Place' focused on three contrasting study areas of early modern London, Cheapside, Aldgate and Clerkenwell, each with a different developmental history and to some extent a different set of sources, in order to recover a wide range of experiences.

Family and household

Early modern London had a strong conception of the 'householder', the core unit in society, responsible for discipline within the household and for the household's relations with the wider world - for example, for the payment of rent, rates and taxes. The householder was usually imagined as male, a citizen and company member, and probably as married with dependents, exercising a patriarchal authority over wife, children, apprentices and servants, and playing a key role in local government and the maintenance of social stability. In practice, many households were headed by women, usually widows, who likewise had authority over and responsibility for their dependents, but were less able to play a public political role. A key question for the project is whether the traditional household of the kind described above was equally prevalent at the beginning and end of the period studied, or whether household size and composition were changing, perhaps in the direction of smaller and more atomised units.

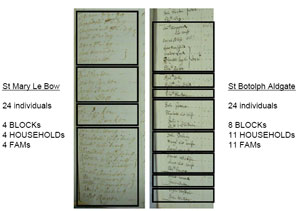

1695 Marriage Duty assessments: domestic group

comparison between

St Mary le Bow (Cheapside)

and St Botolph Aldgate

Larger image (240KB)

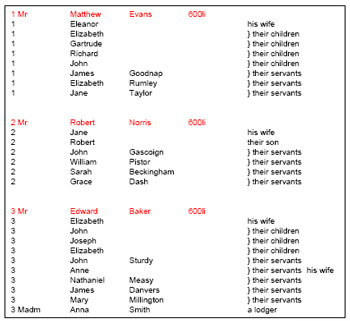

Comparison of the characteristics of family and household in city-centre Cheapside, inner-suburban Aldgate, and suburban-rural Clerkenwell reveals some interesting parallels and differences, with accompanying insights into change over time. A detailed picture of city households at the end of the seventeenth century is available to us, thanks to a novel tax imposed by government on 'vital events' (births, marriages and deaths) in 1695. Commonly referred to as the 'Marriage Duty Tax', the assessments listed every head of household in England, in theory, together with his or her dependents, parish by parish. Analysis of assessment lists for four Cheapside parishes and one precinct in Aldgate points to a city centre/suburban divergence in ways of living. At the most basic level, the returns indicate that each householder answered for an average of 6.6 persons in Cheapside and only 4.8 in Aldgate. In both areas the average number of children per couple (whether that couple was still represented by both parties or by a lone parent) was similar; the difference in household size arose because Cheapside households had more apprentices and servants, and because single parents were more than twice as common in Aldgate. Aldgate also had a slightly higher proportion of single adults in the population. Although no single source offers us this level of detail on household composition at an earlier period, several more limited sources suggest that the differences visible in the 1690s had a long history. A survey of the poor in St Botolph Aldgate in 1636 indicates that small and fragmented families and a large number of single adults were already to be found there. Ship Alley, for example, one of many alleys and closes in the parish, contained sixteen households, including four couples with children, five childless couples, two households of two 'aged' women living together, and one single man and four single women, two of them widows. Apparently only three households in this group were in employment; the rest were unable to find work or too old to work.

Going further back, a survey of the Cheapside parish of St Mary Colechurch in 1574 indicates that the average number of communicants (adults, apprentices, servants, lodgers, and any teenage children at home) per household was 5.4. Mean household size, therefore, counting all children, was probably over 7, slightly higher than the 1695 mean for this area. Married men predominated as householders (only two of 40 households were headed by widows), and only one householder had a parent living with him. There were at least 30 servants, and probably 60 or more, and other sources confirm the presence of apprentices, so there appears to be much in common with the household of 1695.

Marriage and family formation

Another area in which contrasting patterns emerge is that of marriage. Historians have already established that age at marriage in London varied socially and over time, and the parishioners of Cheapside and Clerkenwell bear this out. Men of the merchant and professional class - predominant in Cheapside - married comparatively late, as a result of the long apprenticeship and training that they undertook. First-time bridegrooms were usually in their late 20s, but they married younger women, aged perhaps 20 or 21. By the late seventeenth century contemporaries were worried that some men were not marrying at all, able to live a comfortable existence as wealthy bachelors, and it is true that single men aged over 25 formed over 20 per cent of Cheapside's adult population in 1695, over one-third of them in the upper tax bracket. Many lived as lodgers in larger households, like Gerard Townesend, gentleman, who lodged with the family of William Smith, barber, but others, like Timothy Langley, a wealthy drugster, had their own household with apprentices and servants.

Clerkenwell couples tended to be closer in age, and in their mid-20s when they first married: both men and women needed several years of earning before they could afford to marry, but labourers and tradesmen reached their peak earning potential sooner than merchants and did not need to wait to build up a business before marrying. The increasing proportion of women in London's population in the seventeenth century may have contributed to a very slight fall in the age of first marriage for men. At the same time, though, it appears that marriages in Clerkenwell were more liable to postponement in times of economic crisis or hardship. Sharp fluctuations in the mean age at marriage for females also suggest that economic conditions had a greater effect on female nuptiality than male.

Over time, the tendency for couples to wed outside their parish of residence increased. This may be seen as the expression of a growing desire for personal privacy and a retreat from communal involvement in the marriage process. But whereas the Cheapside parish churches, particularly St Mary le Bow, became popular wedding destinations for people from all over London (thus greatly inflating the number of marriages recorded in the registers), Clerkenwell parishioners increasingly chose to wed outside their own parish, often in the precincts of the Fleet prison. Fleet weddings were irregular but not illegal, and may have been chosen for quickness and cheapness as well as privacy, but careful matching of marrying couples to subsequent births suggests that a higher proportion of them involved cases of fairly late prenuptial pregnancy. Marriage was, in theory, for life, but many marriages were cut short by the early death of one partner, by accident, disease, plague, or childbirth. In such cases it was common for men, and fairly common for women, to remarry quite speedily, reconstituting the family round a new spouse. In Clerkenwell, 40 per cent of widowers who remarried did so within a year of their wife's death. Nevertheless, over-hasty remarriage provoked caustic comment from the parish clerk of St Botolph Aldgate, who noted that Marie Scarlett had 'continewed a widow ten weekes' before her remarriage in 1623, while John Collier, a musician, remarried three weeks after the death of his wife in 1617: 'he would have bene maried soonener, but that he was loth to be at the charg of a license'. Poorer older women, however, were less likely to remarry, especially by the late seventeenth century, and poor widows with several young children found it especially hard.

Sex before marriage certainly occurred, as both prenuptial pregnancy and illegitimate births indicate, though as noted below, these were lower than might be expected. The busy Act Books of the London church courts in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries indicate both that sexual misconduct (fornication, adultery) was not uncommon, but also that many in the community found it unacceptable, and were prepared to call their neighbours to account. Conversely, false accusations of whoredom or unchastity often led to suits for defamation. By the later seventeenth century, there was anxiety that immorality was increasing. The contemporary writer Gregory King thought that London saw 'more frequent fornications and adulteries', and 'a greater luxury and intemperance' than other societies. Evidence from church and criminal courts suggests that the marriage bond was more fragile than it should have been, with many cases of adultery, desertion, self-divorce, and unmarried cohabitation. Bigamy cases confirm the contribution of irregular and clandestine marriage locations (St James Dukes Place, Holy Trinity Minories, and the Fleet) to a more fluid and uncertain condition for marriage. They were often hard to prove, however, and Matthew Dowtey was acquitted at the Old Bailey in 1694 of having married Sarah Suddrey at St Mary le Bow and subsequently Ann Padle at the Fleet chapel, despite evidence from a Fleet minister of the second marriage and of others of his cohabitation.

Births, baptisms and foundlings

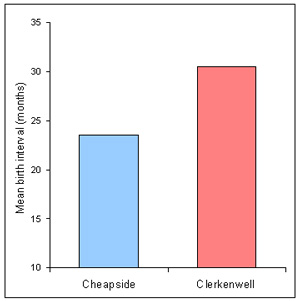

Earlier work on London families and demography indicated that, while a relatively low proportion of the London population was married, marital fertility was comparatively high, with short intervals between births and quite large numbers of children. Although family mobility makes it hard to establish the total number of children born to a marriage in most cases, in a limited but significant number of instances (80 cases in Cheapside, over 2,000 in Clerkenwell) family reconstitution allows us to link a marriage with the baptisms of children and the eventual death of one of the spouses. Comparing completed family cycles of this kind shows that families in the city centre averaged more births than those in the outer suburbs. Parity (the number of births to a marriage of known length) in Clerkenwell increased from a mean of 2.55 in the later sixteenth century to 2.82 in the early eighteenth, while it remained at 4.1 for Cheapside throughout the period. Higher parity in Cheapside was due to younger age at marriage, shorter birth intervals, and possibly better adult mortality prolonging the length of marriages.

Mean intervals (in months) between births, Cheapside and Clerkenwell

There was a noticeable variation in mean birth intervals between Cheapside and Clerkenwell. Cheapside mothers had babies an average of 21-25 months apart, while Clerkenwell mothers averaged 30-31 months between babies, close to the national average for the time. This is very likely due to the practice of wet-nursing, since women who did not breastfeed were likely to become pregnant again more quickly. Wet-nursing was prevalent among wealthier and middling groups but not among the poor. Some parents, like the city officer Richard Smyth of Old Jewry, had their babies nursed in the city, not too far from home, but it was common to send them to rural villages outside London.

Outside the reconstitutions of completed marriages, there are plenty of examples of parents baptising four, five or more children. The highest number born to the same parents seems to be the fifteen infants born to William and Constance Harrison of Cheapside between 1671 and 1694. But parents were very unlikely to raise all, or even most, of a large number of children to adulthood. High and increasing rates of infant mortality mean that actual family size was much lower than the number of births would suggest. The historical demographer Roger Finlay calculated that barely half of all children born in later sixteenth/early seventeenth-century London survived to age 15, and in the later seventeenth century an even lower proportion made it to that age. Certainly at least ten of the Harrisons' children died young.

Snapshots of family and household composition such as the Marriage Duty assessments conceal numerous tragic stories. John Baptist Peters, an attorney living in Bow Lane, had three children alive and at home in 1695, but had already buried seven. Samuel Palmer, James Lever and William Newell and their wives appear as childless couples in that listing, but Samuel Palmer and his wife had buried seven sons between 1683 and 1693; James Lever had buried his first wife and four children; William Newell had also lost his first wife, after a marriage lasting four years, in which she had borne two stillborn children and died giving birth to a third.

Every parish register records the occasional illegitimate birth, but the overall incidence of illegitimate births and premarital conceptions in London seems to have been surprisingly low. Rates of prenuptial pregnancy calculated for eighteenth-century Clerkenwell were lower than the prevailing rate in England, while illegitimate births made up less than 1 per cent of all registered births. Parish records sometimes note the removal of pregnant stranger women lest they give birth in the parish and become a charge on the poor rate ('for getting a great-bellied woman out of the parish. 10d.'). Some single mothers and no doubt other poor women were constrained to abandon their babies, though they often chose a prominent place to leave them, such as the doorstep of the ward Alderman or a local notable, hoping the child would be noticed and rescued. Such babies were often named after the parish or place they were found. A foundling taken up in the entry to the house of Mr Brown, a merchant, in St Pancras parish, was christened Browne Pancrase; five children left in All Hallows Honey Lane at different times were given the surname Honey or Honey-lane; foundlings in St Mary le Bow were given names like Innocent, Fortune, or Repentance, and surnamed Bow, le Bowe, Cheape, or even Street.

By the later seventeenth century, commentators feared that these problems were on the increase. War and economic crisis produced hardship and distress, especially for the poorest; actual illegitimacy totals were rising, from a mid-century low, and child abandonment likewise seemed to be spiralling out of control. As many as a thousand children could have been abandoned each year in London in the 1690s. Wealthier and main-street parishes, like St Mary le Bow, experienced a high number of abandonments, baptising an average of eight foundlings per decade before 1680, rising to 21 and then 59 per decade by the 1710s. Foundling numbers in Clerkenwell increased in line with rising population levels, but never exceeded 20 per decade, in a population ten times the size of St Mary le Bow's.

Apprenticeship and service

One of the main contributions to London's population growth in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries was the migration of young men in search of placement as an apprentice with a citizen master. It has been estimated by the historian Steve Rappaport that an average of 1,400 young men took up apprenticeship every year in mid-sixteenth century London, and that apprentices made up nearly 10 per cent of the capital's population. They joined the city companies, especially those trades focused on clothworking, and formed an especially high proportion of the urban population in the city centre. Even in 1695, when apprenticeship was relatively less important in London as a whole, apprentices made up 10.5 per cent of the recorded population in St Mary le Bow in Cheapside, with 46 out of 105 housefuls containing at least one apprentice. In the inner suburbs under the City's control, including Aldgate, manufacturing was still important, and apprentices probably made up 8-9 per cent of the population. But apprentices were particularly a feature of organised, craft-based, domestic workshop production, and London's expanding economy was coming to rely far more on waged or casual labour, especially in new industrial processes, transport, and the maritime trades. Population growth beyond the bounds of the City also weakened the city companies' grip on manufacturing, and formal apprenticeship was less common in the outer suburbs. The seventeenth century saw major growth in the service sector of London's economy, in all areas from professional to personal.

Households in St Mary Colechurch containing male and female servants. (Marriage Duty Act, 1695)

Larger image (94KB)

The growth of domestic service certainly had a great impact on family life and household composition in the wealthier middling classes, while offering work opportunities for (mostly) younger single women from the poorer classes. There were domestic servants in the sixteenth century and earlier, of course, but their numbers increased greatly in the seventeenth. Three-quarters of households in the Cheapside parishes had one or more female servants in 1695. Some of London's army of maidservants would have been born in the capital, perhaps in poorer suburban areas like Aldgate and Clerkenwell, but most would have been migrants and few came from, or stayed long in, the parishes in which they served. The suburbs over all had a much lower proportion of households with domestic servants: in Aldgate only 16 per cent of households had female servants in 1695.

Male domestic servants were much less common than females, perhaps only a quarter of the number. Some worked indoors as footmen or footboys but others may have been grooms or private coachmen. Employing a manservant was a mark of higher wealth and status, as was the fashion for young black servants. Thomas Gardiner, surgeon of the king's household, lived in St Mary le Bow in 1695 with his wife and daughter, two apprentices from wealthy families, a coachman, two maidservants, and a 'blackboy' called Toby. Another householder in nearby Ironmonger Lane had four servants and 'Simon his black'. Some black servants were also noted in the registers of St Botolph Aldgate, but others were apparently wage-earners or lived independently as lodgers and tenants.

Housing and accommodation

An important cross-bearing on the experience of family and household is gained by considering them in relation to the accommodation they enjoyed. Different housing types predominated in Cheapside and Aldgate, and may indicate different ways of living.

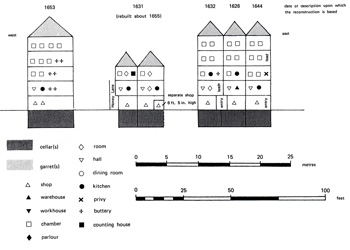

Diagrammatic elevations of 17th-century properties on the Cheapside frontage (All Hallows Honey Lane parish).

Larger image (120KB)

Street-front houses in Cheapside before the Fire of 1666 were an early, timber-framed version of the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century London terrace or row house, with two rooms on four or more floors and outbuildings behind. A shop or workshop occupied the ground floor, and the main living room, called the hall or later the dining room, was on the first floor, with chambers and garrets above. Houses like this would have five or six hearths, internal privies, and in some cases piped water; rooms were panelled or hung with painted cloths, and the large windows were glazed. Though adjoining houses were similar in type, they differed in detail, being owned separately and built and rebuilt at different times; high rental values justified investment in maintenance and frequent refurbishment and improvement. Soaring property values encouraged building upwards and extending houses backwards over yards, but housing quality remained high and families were not too overcrowded. Smaller houses in the side streets housed artisans and craftsmen, though there were also several large houses set back from the street in private courts or closes.

Aldgate also had some substantial houses along Houndsditch and the Minories, as well as a number of inns in the High Street, conveniently situated for travellers from and to Essex and East Anglia. In 1550 there was plenty of space in the parish, but as population pressure increased, existing houses were subdivided and gardens, backyards and open spaces were built over with cheap, low-rise housing, forming a network of alleys and closes. Because of their lower value, such dwellings were rarely described in the detail available for the Cheapside properties, but it is clear that they usually had not more than two or three rooms, and the occupants shared their water supply and privies with other neighbours. They were cheaply and often shoddily built - some were no more than converted sheds and stables - and were altered and subdivided in piecemeal fashion. Their inhabitants included families with children, single working people, and many old and poor individuals, often sharing accommodation. By the 1630s the parish had many developments of this kind, listed as alleys, rents, or tenements, but population and density nearly doubled by the end of the century. Although Aldgate escaped the Fire of 1666, the displacement of population from the central areas no doubt added to its problems, pushing up demand and rents.

The Hearth Tax returns of the 1660s allow comparison of housing sizes across all three sample areas. Not every room had a fireplace, of course, but the number of hearths per dwelling is a fair indicator of relative size and spaciousness. Predictably, the mean number of hearths per dwelling was highest in the Cheapside parishes (5.4) and lowest in Aldgate (2.5), with Clerkenwell between the two at 3.3. Clerkenwell had a variety of housing, with some substantial dwellings, but a growing number of streets of small houses.

Environment and health

An element of the picture of family, household and housing that merits further examination is health. Births and deaths shape the family, and are themselves partly determined by local factors; the physical circumstances of the household (its living accommodation, local services, neighbourhood characteristics) have a significant effect on its healthiness.

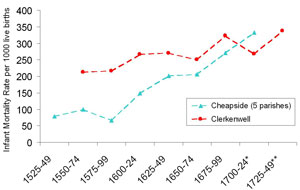

Death rates in early modern London were high, with plague, smallpox, and consumption killing many adults before middle age. One of the most significant elements in the mortality profile, however, was the poor (and worsening) survival of babies and infants. Family reconstitution and analysis shows a marked rise in infant mortality (deaths under one year old) in the later seventeenth century. Infant mortality was already high in Cheapside in the later sixteenth century, but increased over time to reach 286 per thousand live births in the later seventeenth century and just over 350 per thousand in the early eighteenth. Clerkenwell, poorer than Cheapside in most respects, initially had a higher but more stable rate of infant mortality, of about 200-250 per thousand until the mid-seventeenth century, after which the rate climbed to reach well over 300 per thousand by 1700. Worsening infant mortality in the outer suburbs no doubt owed much to increasing population numbers and density, but the fact that rates continued to rise in the inner city, despite the renewal and improvement of the urban fabric after the Fire of 1666 and the decline in city-centre population, is striking.

Plague, London's most famous killer disease, varied in its impact by time and place. The epidemic of 1563 may well have been the worst of the early modern plagues for the Cheapside parishes, and the worst for the city centre over all, but Clerkenwell, sparsely populated at the time, does not seem to have been badly hit. The first noticeable plague epidemic in Clerkenwell was in 1593, when the Cheapside parishes also suffered. The epidemic of 1625 was severe in Aldgate and Clerkenwell but more muted in Cheapside, while that of 1665, the last 'great plague', was severe in all three areas but particularly so in Aldgate and Clerkenwell. 'Worst' is a relative assessment, based on average annual mortality totals: the numbers dying in 1665 were much greater than in any previous epidemic. According to the Bills of Mortality, the five Cheapside parishes buried 142 people in 1665 (73 of these deaths being attributed to plague), Clerkenwell 1,863 (1,377 of plague) and St Botolph Aldgate 4,926 (4,051 of plague). In the metropolis as a whole, 97,306 deaths were recorded, with 68,596 of them attributed to plague.

In addition to the major plague epidemics, there could be local outbreaks, confined to one or a few neighbouring parishes: St Pancras in Cheapside suffered outbreaks in 1542-3 and 1547-8, while adjoining parishes were spared. The brief sweating sickness epidemic of 1551 had relatively little impact, but all the Cheapside parishes experienced some increase in mortality in the influenza epidemic of the later 1550s. Few other causes of death, epidemic or otherwise, are indicated in the Cheapside or Clerkenwell parish registers, but those for St Botolph Aldgate are full of detail for the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, as T.R.Forbes's study Chronicle from Aldgate (1971) shows. Apart from infantile causes of death, and plague, the major killers were consumption or pulmonary tuberculosis and smallpox, with 'fevers' also important. Different diseases affected age-groups differently. The disease categorised as 'ague' (from febris acuta, a sharp fever), which was possibly malaria, possibly influenza, or possibly both, caused 17 per cent of the deaths of those in their 20s, but less than 6 per cent of those in their 60s, and hardly any of those over 70. Smallpox also tended to kill younger persons (survival does confer immunity), but consumption, while affecting all ages, accounted for an increasing proportion of deaths in each age group from the twenties (26 per cent of deaths) to the seventies (58 per cent of deaths). Dropsy killed few people in any case, and none aged under 20; it affected those between 50 and 70 worst.

Conclusion

The small size of the biological family group that we see in early modern London was the result of both social practices and mortality. The youngest child or children of a family might be away at nurse; children at home were quite likely to have lost brothers or sisters; teenage children were often out in the world, seeking education, training or employment. Many adults married relatively late. There were few three-generation families under one roof, perhaps not surprising since so many Londoners were themselves first-generation migrants. But household groups could be quite large, with resident servants and apprentices, while single lodgers and lodging families filled out the houseful. What we often think of as the classic 'family' - parents and children - accounted for a limited proportion of the population, being surrounded and complemented by numerous singletons, pairs, and fragments of families. Although we can see some development of family forms and formation, several of the differences between areas visible at the end of the seventeenth century seem to have been established several decades earlier. Cheapside seems little changed by the Fire and rebuilding. However, given that more of London was like Aldgate and Clerkenwell, it may be that we should look to these areas for a better understanding of the new metropolitan society emerging at the end of the seventeenth century.