Welfare provision in Finland in the 19th and early 20th Centuries

Pirjo Markkola (Abo Akademi University, Finland)

The Poor Law and charity are the historical cornerstones of welfare provision in most countries. In Finland the Poor Law was based upon a long tradition of local administration and local funding. Until 1809 Finland was part of the Swedish kingdom and shared its legal and institutional system. As a result of the Napoleonic wars, Finland was attached to the Russian empire as an autonomous Grand Duchy. However, the Swedish legal system and legislation still applied in Finland, and the Lutheran Church was still the established church. In 1917 Finland gained independence. (1) In this article, I will briefly introduce the various forms of welfare provision in Finland. (2) I focus on the early history of welfare, i.e. on the period before the Second World War.

Parish poor relief

Since the Reformation, poor relief was organised by the Lutheran parishes which, in fact, were the only local administrative bodies in rural areas. The pattern was enabled by religious homogeneity. The local community had to take care of its own poor, but the state dictated the organising of poor relief. A division of labour between the state and the local authorities developed relatively early. Poor relief, child care and moral education belonged to the parishes, whereas the care of the incurable sick, the control of the able-bodied poor and punishing the vagrants, were regarded as matters for the state. The poor who were not employed were treated as vagrants. Male vagrants were sent to workhouses or forced to do military service; female vagrants were placed in workhouses for women.

Moreover, migration was restricted. Parishes could forbid the poor or even the potential recipients of poor relief to settle within their borders. Some landowners were prevented from recruiting servants from other parishes when the parish meeting suspected that the new parishioners might become an economic burden.

During the 19th century, the population of Finland doubled. The number of landless farm labourers increased rapidly. This deepened rural poverty and underemployment. With the restrictive legislation, the situation of the poor became complicated. The old paternalistic order in which the poor were under the control of their employers faced growing difficulties. New instructions to eliminate beggary were issued and the state authorities tried to combat social problems. The governors were to control the local poor relief and promote private charity.

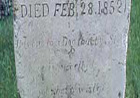

In the 1840s, a state committee to prepare for administrative poor relief reform was established. The committee report resulted in the Poor Law of 1852 establishing compulsory local taxation and making local boards for poor relief mandatory. The Poor Law emphasised paternalistic relations. The primary provider of maintenance was the family; the employers had to maintain their aging servants. Those entitled to poor relief included children in need of protection, the insane, the disabled and the aged infirm. Moreover, the old, sick or disabled people who were able to work and the poor in need of temporary support were entitled to public support. Nevertheless, the able-bodied poor were expected to earn their assistance by working for the community.

The principles of the Poor Law seemed to be generosity and control: everyone in real need of help had the right to receive it, but the recipients of poor relief were subject to the control of the parish. The seeming generosity of the Poor Law cannot be understood without paying due attention to the Act on Forced Labour and Vagrancy in 1852 which restored compulsory service for the poor. Both laws re-established the old paternalistic order in the spirit of the 18th century. (3) By subjecting the lower classes to paternalistic control, the state tried to resolve the problems of poverty and the threat of social unrest. However, the Poor Law of 1852 was born outdated. The old patterns did not function anymore. The old conception of protection was giving way to the belief that a free labour force was the best remedy against poverty.

Growing criticism of the Poor Law led to revisions in social legislation. In the 1860s, new laws concerning compulsory service and vagrancy were passed. Many restrictions in migration and the connection between unemployment and vagrancy were abolished. In an industrialising society the principles of the Poor Law were seen as entirely unacceptable. The authorities were urged to find new solutions to poverty and the organisation of welfare.

Municipal poor relief

The new local administration was established in 1865 with the separation of the parishes and municipalities in rural areas. The relatively strong autonomy of the parishes developed into the basic structure for municipal self-government. In the new division of labour, poor relief and basic education became the responsibilities of the municipalities. However, municipalities soon met huge problems in organising poor relief. As a result of the severe famine of 1867-8, the number of needy people exploded. Many paupers perished, but they were replaced by a great number of orphans and other poor. After the famine, the old poor relief could not be continued.

A committee report preparing new legislation on poor relief, vagrancy and migration was submitted in 1872. The committee wrote very warmly about the particularly good effect of the workhouses on the able-bodied poor in other countries. In 1879, a liberal and harsh Poor Law was passed. The law aimed at replacing the old paternalistic order with the social responsibilities of a nuclear family. Able-bodied men and women were to maintain themselves and their children; husbands were also to support their wives. Access to poor relief was restricted and its recipients were subjected to the guardianship of the municipal authorities.

An important principle was the division between mandatory and discretionary assistance. The mandatory poor relief covered poor minors, the insane, the disabled, the chronically sick, and the old and infirm poor. Temporary need was no longer acceptable. For discretionary relief municipalities were to build workhouses where the poor should engage in forced labour. An explicit aim was to discourage the poor from seeking poor relief. The able-bodied poor were to maintain themselves and their families. Middle-class family values were introduced to the working class and social legislation was a tool to develop a civic society in which citizens were free to support themselves on the free labour market.

Finland was not exceptional in its reforms. The direct model was taken from the Swedish Poor Law of 1871, but the Danish and the Norwegian Poor Laws in the 1860s had also followed similar principles. Actually, the English Poor Law of 1834 with its liberal ideas of economic well-being as an individual's own concern provided a common model.

Insurance policies

As soon as the labour relations were liberalised, attempts to regulate them actualised. The modern welfare policies attempted to tackle the problems of the industrial working class: the loss of income through accident, sickness, unemployment and old age. One solution was social insurance, a new institution which broke with the principles of the Poor Law. In 1889 a committee to investigate social insurance was nominated. As a result, the Employers' Liability Act was passed in 1895. The Act aimed at the protection of industrial workers against industrial accidents, but sickness insurance and pensions were left on a voluntary basis.

At the same time industrial workers started to establish various forms of mutual aid organisations including sickness funds, relief funds and trade unions. Many societies were based on an insurance principle according to which the membership fees entitled the members to assistance in cases of accident, sickness or unemployment. In 1897 the administration of the mutual aid societies was prescribed by law. Sickness funds became the most common providers of mutual aid among industrial workers. Moreover, numerous self-help circles or friendly societies were founded. Women were a majority in the general mutual aid funds and self-help circles but were barred from many factory funds. (4) Mutual aid societies and self-help organisations provided a voluntary insurance against various risks.

Philanthropy and Christian charity

The reluctance of the local administration and the state to assume responsibility for everyone in need of care created a need for voluntary social work, philanthropy and new political initiatives. Philanthropic associations emerged from the 1830s onwards. (5) The Ladies' Societies established schools for poor girls but also helped the lower classes to help themselves by arranging employment for poor women. Many associations, e.g. the city missions, worked on a religious basis; however, the philanthropic principles of self-help informed their work. Some religious organisations included men in their programmes, whereas the Ladies' Societies mainly chose to help women and the children of the poor. The experienced female philanthropists engaged also in statutory welfare provision. The prevalent conceptions of gender difference paved the way for women in public decision-making.

Within Christian charities new ideas on preventive aid were developed. Following the German pattern, two deaconess institutions were founded in the 1860s. The ultimate goal of the diaconal work was to revive popular piety, but the goal was to be achieved by alleviating earthly suffering. The main form of work was to nurse the sick poor, but deaconesses involved also in education and social work among the poor. They were employed by charitable associations, municipalities, the Lutheran parishes and the state-run social institutions. Moreover, the deaconess institutions pioneered in the education of nurses and public health nursing.

Social policy

In December 1917 Finland became independent. However, a civil war broke out in January 1918. After the short, bitter war, approximately 25,000 children needed care, the majority being the children of the socialists. Families on the White side were provided with pensions, but the orphans of the Red soldiers were subjected to poor relief. Several orphanages were established; additionally, the state provided voluntary organisations with state subsidies for child care institutions. The state intervention in working-class families gave an impetus to the social policy of independent Finland.

The new Act of Poor Relief was passed in 1922. It was an improvement in the making of social security as it broke away from the old spirit of the Poor Laws. The new law expanded entitlement to poor relief. If someone was not able to support him/herself or to get maintenance from the family, the municipality was to help. Some old methods such as the circulation of the poor and pauper auctions were forbidden. Outdoor relief, i.e. cash payments to the poor, was preferred. In practice, institutions continued to be the most common forms of relief. Moreover, the extensive control practised by the authorities was continued. The emphasis on the institutional care and the intensive control of the recipients of the indoor aid indicate that the Civil War put its stamp on the ways in which the poor were treated in a young nation.

Civil society had a crucial role in social work during the inter-war period. The Civil War widened the division between the charity practised by the winners and the self-help of the socialists. On the charitable side many associations engaged in social work. Additionally, employers provided their employees with social services. The diversity of welfare provision continued during the inter-war period.

The end of the 1930s opened up a new era in social legislation. Comprehensive reforms were undertaken in 1936 and 1937. Child welfare, the care of vagrants and the care of alcoholics were separated from poor relief. Social administration and the division of labour between the state and the municipalities were both redefined. Moreover, the 1937 modest pension reform gradually introduced the principle of national insurance to social legislation. Yet, other forms of social insurance, such as sickness insurance and employment pensions, were to wait until the post-war era.

Notes:

- On Finnish history, see O. Jussila, S. Hentilä and J. Nevakivi, From Grand Duchy to a Modern State. A Political History of Finland since 1809 (London, 1999); D. Kirby, A Concise History of Finland (Cambridge, 2006); J. Lavery, The History of Finland (Westport, 2006). Back to (1)

- On the history of poor relief in Finland, see M. Satka, Making Social Citizenship. Conceptual practices from the Finnish Poor Law to professional social work (Jyväskylä, 1995); Austerity and Prosperity. Perspectives on Finnish Society, (ed.) M. Rahikainen (Helsinki, 1993); Gender and Vocation. Women, Religion and Social Change in the Nordic Countries, 1830-1940, ed. P. Markkola (Helsinki, 2000); P. Markkola, 'Changing patterns of welfare: Finland in the 19th and early 20th centuries', in Welfare peripheries. The Development of Welfare States in 19th and 20th Century Europe, ed. S. King and J. Stewart (Bern, 2007), pp.207-30; P. Pulma, Fattigvård i frihetstidens Finland. En undersökning om förhållandet mellan centralmakt och lokalsamhälle (Helsinki, 1985). Back to (2)

- This has been pointed out by the Finnish historian Panu Pulma. Back to (3)

- J. Jaakkola, 'Mutual benefit societies in Finland during the 19th and 20th Centuries', in Social Security Mutualism, ed. M. van der Linden (Bern, 1996), pp. 501-25. Back to (4)

- On philanthropy and charity in Finland, see A. Ramsay, Huvudstadens hjärta. Filantropi och social förändring i Helsingfors - två fruntimmersföreningar 1848-1865 (Helsingfors, 1993); P. Markkola, 'Promoting faith and welfare. The deaconess movement in Finland and Sweden, 1850-1930,' Scandinavian Journal of History, 25 (2000); Gender and Vocation. Women, Religion and Social Change in the Nordic Countries, 1830-1940, P. Markkola (Helsinki, 2000). Back to (5)