The welfare of the vulnerable in the late 18th and early 19th centuries: Gilbert's Act of 1782

Samantha Shave (University of Southampton)

Workhouses have long assumed a central place in studies on the poor laws. While we know that the majority of relief claimants were actually given outdoor relief in money or in kind from the parish pay-table, welfare historians have shown that many individuals entered workhouses during moments of both short and long-term need. This dynamic has a long history. The Elizabethan poor laws permitted parishes to find accommodation for ‘poor impotent people’ in addition to the requirement to ‘set to work’ their poor. By the end of the 17th-century, however, some cities had obtained their own ‘Local Acts’ which contained specific legislation designed for the specific welfare needs of that locale. Central to these Acts was the workhouse. The first Local Act was passed in 1696 for the Civic Incorporation of Bristol. Throughout the next couple of centuries both rural and civic incorporations were formed, usually consisting of a group of parishes sharing the same workhouse. These workhouses were run according to the specification of their Local Act, though in practice subsequent local decisions were just as important in determining relief policies.

Subsequent ‘enabling’ legislation allowed individual parishes to implement a workhouse system without recourse to parliament. Knatchbull’s Act of 1723 allowed parishes to stipulate that those who required relief had to go into the workhouse and work for the parish in return. (1) Passed at a time when both the number of paupers and the cost of poor relief had started to increase, the Act effectively made claimants contribute directly towards their own maintenance costs. According to Anthony Brundage, the Act contained ‘one of the two linchpins’ of the later infamous Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834, namely the workhouse test. (2) Both Knatchbull’s Act and the Amendment Act of 1834 engineered a welfare system whereby the workhouse acted as a deterrent: the poor would only enter the house – and thereby receive relief – as a last resort. While the Act of 1834 did not make the creation of workhouse-centred unions compulsory, in practice the zealous activities of the Poor Law Commission - the London-based welfare authority responsible for the central administration of the New Poor Law - meant that very few places fell outside of their control by the late 1830s. The Commission instructed that parishes formed into unions, ideally around a market town or city, with the bulk of welfare provided to the poor within a central workhouse. Thus within 300 years, maintaining the poor within a workhouse went from being a policy which was adopted at a parish’s own will to a legal requirement.

In the history of the workhouse, however, one piece of legislation has received little attention: Gilbert’s Act of 1782 (22 Geo. III, c.83). The private Act, drafted and promoted by Thomas Gilbert, empowered parishes to provide a workhouse exclusively for children, ‘the Aged, Infirm, and Impotent’, i.e. those individuals who were ‘not able to maintain themselves by their Labour’. (3) Parishes could also unite for the provision of relief under this legislation, as long as each parish was within ten miles of the workhouse. Much of the voluminous literature on the poor laws mentions Gilbert’s Act, but such references are only tacit acknowledgements of its impact upon the lives of the poor. (4) In comparison, other types of workhouse have received more systematic treatment. In particular, a significant number of studies have examined the set-up of New Poor Law unions and the conditions experienced by such workhouse inmates. (5) Such studies cannot be meaningfully made to illuminate the welfare provided in pre-1834 workhouses because of the differing principles which underpinned the operation of early workhouses in comparison to those established under the New Poor Law. The role of the workhouse in Gilbert’s unions – or parishes – was premised on diametrically opposed principles to that of post-1834 workhouses: a Gilbert’s workhouse was intended to be ‘a source of care, not deterrence’. (6)

Anne Digby’s study of Norfolk is the only work which has thus far examined the adoption of Gilbert’s Act. The focus of Digby’s research though was the assessment of the impact of the 1834 Act on the operation of the poor laws in the county rather than an analysis of Gilbert’s Act per se. (7) Consequently the few comments on the Act are not well grounded in observed histories. Dorothy Marshall, for example, claimed that Gilbert’s Act marked the start of ‘a new wave of humanitarian feeling’ in England. (8) Others, conversely, have argued that this period is characterised by quite the opposite feeling, supposedly due to the hostile attitudes of the landed elite towards the poor and the ‘greediness’ of farmers. (9) Such contradictory statements graphically demonstrate the need for further work to better place Gilbert’s Act within the longue durée of ‘modern’ welfare history.

The lack of research on Gilbert’s Act is even more surprising considering that workhouses disproportionately affected the welfare of the ‘vulnerable’ poor in the 18th and 19th-centuries. Due to the semi-autonomous powers of the vestry, a wide spectrum of locally-determined policies could have been linked to early parish workhouses. Many of these impacted on particular groups of the poor such as children and the elderly. For instance, in west Kent between 1700 and 1750 many vestries ordered that the elderly in particular should enter a workhouse rather than receive a parish pension. (10) At the same time, the parish of Puddletown, Dorset, decided to have a child-only workhouse. (11) In addition, during the New Poor Law the largest proportion of workhouse residents were those typically from vulnerable groups. (12) Notwithstanding the fact that being young, old, unwell, disabled or a parent while in poverty has received much recent attention – for instance Pat Thane’s and Susannah Ottaway’s histories of old age have highlighted how the elderly got by with and without the aid of the statutory welfare system – Gilbert’s Act is only ever mentioned in passing. (13)

In view of this lacuna, this short paper presents a brief case study of one Gilbert’s Act workhouse, that of Alverstoke in Hampshire. While it is difficult to make universalising statements from one case alone, an examination of Alverstoke’s experience demonstrates that a wealth of information can be obtained about the operation of Gilbert’s Act and how it impacted upon the lives of the poor. Before analysing the Alverstoke evidence however, it is necessary to understand the motivations of Gilbert and the policy stipulations of his Act. I then explain why welfare under the Act has thus far been neglected and how it has gained the reputation, in a few studies which do exist, as a contested welfare setting. This paper then suggests that where Gilbert’s Act was adopted and implemented it had a significant impact on the welfare provision of the vulnerable. The conclusion will outline further research questions.

Thomas Gilbert and the Act of 1782

Born in Staffordshire, Gilbert was a chief land agent to Lord Gower and a keen poor law reformer. Through his work, he developed an immense political, legal, commercial and industrial knowledge which enabled the Gower estate to become one of the most prosperous in England. Gilbert’s concern for the poor may have stemmed out of his role as agent, which had allowed him to take onboard the role of paymaster for a charity of naval officers’ widows. In November 1763 he was elected to Parliament for Newcastle-under-Lyme and subsequently represented Lichfield until his retirement in 1794. (14) According to Coats, Gilbert’s enthusiasm for poor law reform and especially his desire to improve the welfare of the poor was immediately apparent on his arrival at Westminster and within a month he threw his energies into better understanding the workings of the poor laws. Between January and March 1764 he sat on a committee which sought to ‘resolve’ the debt of the Gloucester workhouse. This seemingly self-contained examination soon unfurled into a ‘lengthy dispute in which the merits of indoor and outdoor relief were vigorously debated’. (15) It is thought that in these early years Gilbert had developed his preliminary ideas for the later Act. Indeed, the first bill he issued – for the ‘Employment and better relief of the poor’ – was debated in Parliament in 1765. (16) This early bill proposed that commissioners be appointed to draw up relief districts for which local-level committees would be elected and charged with establishing workhouses for the reception of their poor. The bill failed to gain support though. Gilbert revised these plans in 1775, but, again, this amended bill was rejected in the House of Lords by a majority of seven votes. (17)

There was then something of a turning point in Gilbert’s thinking about relief strategies. (18) In his next pamphlet, published in 1781, he wrote that the ‘vulnerable’ poor – the aged, infirm and young – should be accommodated in the workhouse. The able-bodied would not, however, be permitted to reside in the house. This policy idea was based on the information he gleaned from the 1771 Parliamentary Returns on Houses of Industry. Gilbert noted that while some workhouses had ‘succeeded very well, in Places where they have been duly attended by Gentlemen respectable in their Neighbourhood’, others were much ‘less beneficial’. Their overall success was ‘precarious’. (19) Gilbert thought that such old parish workhouses:

are generally inhabited by all Sorts of Persons … Hence arise Confusion, Disorder, and Distresses, not easily to be described. I have long thought it a great Defect in the Management of the common Workhouses, that all Descriptions of poor Persons should be sent thither; where, for the most Part, they are very ill accommodated. (20)

As Marshall noted, Gilbert thought old parish workhouses were ‘dens of horror’. (21) Such workhouses were too uncomfortable for those who were in poverty due to no fault of their own and places where the young were susceptible to ‘Habits of Virtue and Vice’ learnt from ‘bad characters’. For the sake of both the poor and the rates, Gilbert thought that workhouses should be reformed to promote industrious behaviour. (22)

These ideas culminated in a new bill and the subsequent Act of 1782 which enabled parishes to provide a workhouse solely for the accommodation of the vulnerable. (23) Although such residents were, as Gilbert put it, ‘not able to maintain themselves by their Labour’ outside of the workhouse they were still to ‘be employed in doing as much Work as they can’ within the workhouse. (24) Work was therefore a part of everyday life within a Gilbert’s Act workhouse. The able-bodied were only to be offered temporary shelter and instead were to be found employment and provided with outdoor relief. (25) Those who refused such work (the ‘idle’) were to endure ‘hard Labour in the Houses of Correction’. (26)

How was such a workhouse to be established and managed? Gilbert wanted to allow parishes to unite together so that they could combine their resources and provide a well built and maintained workhouse. According to Steve King, Gilbert’s Act was the first real breach of the Old Poor Law principle ‘local problem - local treatment’. (27) Yet, any ‘Parish, Town, or Township’ was also permitted to implement the law alone, and hence concerns over poverty did not always transcend parish boundaries. (28) Gilbert’s Act workhouses were to be managed in a different way compared to the older parish workhouses. Gilbert believed that the poor laws had been ‘unhappily’ executed ‘through the misconduct of overseers’. (29) Such officers, he claimed ‘gratify themselves and their Favourites, and to neglect the more deserving Objects’. (30) This dim view of overseers was shared by many others at the time. (31) In correction, Gilbert’s Act proposed two new roles which essentially bypassed the overseers’ role in issuing relief: the visitor and guardians. Each Gilbert’s union or parish was to appoint one visitor whose role, similar to that of a Chairman under the New Poor Law, was to bring strategies to the board table, make policy decisions and to give direction to the guardians, parish vestries and workhouse staff. (32) One guardian was to be elected for every parish in a union, or in the case of single parish adoptees multiple guardians were permitted. The visitor and guardians met once a month to organise and administer welfare. Within these meetings they could establish year-long contracts with third parties ‘for the Diet or Cloathing of such poor Persons … and for the Work and Labour of such poor Persons’. (33) Magistrates were also given further powers concerning the establishment and management of workhouses under Gilbert’s Act compared to previous workhouse acts. (34) Where the Act was adopted, therefore, the role of overseers was reduced to that of little but poor rate collectors. (35)

A neglected and contested welfare setting

Minimal attention has been paid to the welfare provided under Gilbert’s Act primarily because it was it was a ‘non-compulsory’ – or ‘enabling’ – piece of legislation. The majority of a parish’s ratepayers had to decide to adopt the legislation before they were able to provide welfare under the Act. This automatically places the Act in the shadow of what came later: the effectively compulsory Poor Law Amendment Act. Consequently, the Act is always purported to have had a limited uptake. Initially this may have been true. The MP Arthur Young, some 14 years after the Act had passed, claimed that ‘very few’ unions had formed. (36) As a more recent study suggests, ‘there was a slow and steady increase in the number of Gilbert’s unions formed during the early nineteenth century’. (37) Roger Wells has also recently stated that many areas adopted the Act in the late 1820s. (38)

There are several estimates as to the number of parishes which adopted Gilbert’s Act. According to the Select Committee on Poor Relief of 1844, there were apparently 68 Gilbert’s unions and 3 Gilbert’s parishes (a total of 1,000 parishes), although a separate return of Gilbert’s unions (1844) lists 76 adoptions (1,075 parishes). (39) The Webbs, however, stressed that there was only a total of 67 unions (total of 924 parishes), while ignoring the fact single parishes could, and did, adopt the Act unilaterally. The overall impact of the Act was, according to the Webbs, ‘relatively trifling’. (40) This statement goes a long way in helping us to understand our lack of knowledge about Gilbert’s Act. As the Webbs together created the discipline of poor law studies, and subsequently influenced many later social histories of social welfare, their interpretations of Gilbert’s importance went unchallenged for many years. For instance, Felix Driver (working on the 1,000 parishes estimate) states that only ‘one thousand parishes containing half a million people’ had welfare administered according to the Act, (41) while Longmate suggests that only about ‘1 in 16’ parishes implemented the Act. (42) Further interpretative problems have arisen from these estimates, most notably concerning the geography of adoption. The Webbs argued that unions were ‘practically all rural in character; the great majority in south-eastern England, East Anglia and the Midlands, with a few in Westmoreland and Yorkshire; none at all in Wales, in the west or south-west of England, or north of the Tees’. (43) Mandler states that the Act ‘was taken up almost exclusively in urban and industrial areas, apart from a unique cluster in East Anglia’. (44) While the geography of the adoption has been interpreted in diverse ways, vast patches of England were, according to these interpretations, untouched by the Act.

The Act, in conclusion, was of local importance at best and was insignificant at worst. Yet, parliamentary returns are a problematic source on which to base entire understandings as to the importance of individual pieces of social legislation. They can be partial, incomplete and offer a mere snapshot of reality. First, doubt surrounds whether those asking the questions knew that Gilbert’s parishes could exist as well as Gilbert’s unions. Second, places which were under the Act may not have returned these details to Parliament. In addition, even though a parish might not have explicitly adopted Gilbert’s Act they may have wittingly or unwittingly adopted the principles of the Act. Finally, returns only capture a process at a specific moment in time. Many Gilbert’s unions and parishes may well have been established, functional and then disbanded before the returns of 1844 were made. Indeed, the Poor Law Amendment Act had been already in operation for nearly a decade when the returns were made.

Records which were created at the local level, therefore, offer a potentially less distorted – and more comprehensive – picture of Gilbert’s adoption. Where they survive, vestry minute books are an important source of this information. Within these books are usually some details of welfare administration and their decisions to implement enabling acts. Workhouse account or Board minute books may also contain notes of an agreement to implement acts. Other sources such as overseers’ account books and magistrates’ agreements can also provide potentially useful information. Evidence as to the adoption of Gilbert’s Act can also be found in newspapers, not least in the form of adverts for staff, the contracting of provisions and reports of Board meetings. Some adoptions can also be discovered in correspondence between the Poor Law Commission, their assistants and the newly formed New Poor Law unions. (45) Through the use of such a wide range of documents, historians have added to those adoptions listed on the returns and continue to discover further Gilbert’s unions and parishes. (46)

As well as the under-estimation of adoptions, much of what we currently know about Gilbert’s Act has been influenced by the Commission. Although the Commission was allowed to form new unions, it had no powers to force parishes acting under Gilbert’s Act to dissolve. In 1835 the Commission asked the Attorney-General what they were able to do regarding those parishes that were providing welfare under Gilbert’s Act. In response, the Attorney-General stated that as the able-bodied under Gilbert’s Act were employed outside of the workhouse rather than within, thus running counter to the ethos of the Amendment Act, the only way of universally abolishing the practice was to seek the repeal of 22. Geo. III c. 83. (47) Yet Gilbert’s Act was not officially repealed until 1869. Consequently, much of what we know about Gilbert’s Act rests upon what happened to Gilbert’s unions and parishes in the struggle to seek their dissolution post 1834.

Roger Wells has highlighted the resistance some Gilbert’s unions and parishes made in the face of overtures from the Poor Law Commission. In his recent paper about parish housing Wells notes that many areas which continued to administer relief under Gilbert’s Act were dominated by ‘anti-Poor Law Amendment grandees’. Significant numbers of parishes under the Act remained in West Sussex, and around the Staffordshire/Derbyshire borders were the Earl of Egremont and Sir Henry Fitzherbert. Both respectively exerted their influence. (48) Egremont was particularly insulted by the actions of the Assistant Poor Law Commissioner Henry Pilkington. The Assistant had ‘formed his unions with a pair of compasses; he knew nothing whatever of the localities of the neighbourhood’. Apparently the Lord ‘was very much annoyed at the manner in which it was done’ and decided to battle with the Commission for the Sutton Gilbert’s union to stay put. (49) It had operated for 78 years before it was compulsorily dissolved on the abolition of Gilbert’s Act. But it was not always the case that Gilbert’s Act parishes and unions stood in the way of the Commissioner’s wishes. The Westhampnett Union was formed in March 1835 from parishes which were previously under Gilbert’s Act. It even became one of the Commission’s ‘model’ unions. (50) This miraculous transformation has been equated to the overwhelming influence of the Duke of Richmond who, as a cabinet minister and large landowner, appointed his stewards and tenants to the Union’s Board of Guardians. (51) Due to the actions of a persistent few landowners, however, the Poor Law Commission was not able to implement the universal welfare system they desired.

The Poor Law Commission frequently complained about the management of those residual parishes under Gilbert’s Act, many such objections being detailed in the Minutes of Evidence of the 1844 Report of the Select Committee on Gilbert’s Act. (52) These contain the interviews of Poor Law Commissioner George Cornewall Lewis, who was appointed as a Commissioner in 1839, in addition to a number of the Assistant Poor Law Commissioners. Lewis thought that the ‘voluntary’ nature of policy adoption had caused ‘extremely irregular combination[s] of the parishes’. In the West Riding of Yorkshire he stated that Gilbert’s unions were formed in a non-contiguous fashion. Distant parishes were within the same union and yet ‘intervening parishes’ had been left ‘ununited’. (53) Post-establishment enlargement of unions led Lewis to doubt the very legality of some Gilbert’s unions. (54) These included the East Preston Union (West Sussex) which was initially formed of five parishes but eventually expanded to nineteen. Another charge made by Lewis was that the magistrates were ‘extremely lax’ in the auditing of Gilbert’s unions and parishes accounts. As such, Lewis contended that the ‘interests of the ratepayers are not sufficiently guarded’. (55) Interesting though the Poor Law Commissioners’ opinions of management of Gilbert’s unions and parishes are, further research is required to examine whether such views represented any observable reality.

Evidently, our current understandings about the adoption of, and practices under, Gilbert’s Act largely derive from the information collected – and subsequent analyses undertaken – by the Poor Law Commission. The next section offers a case study of the operation of Gilbert’s Act in Alverstoke between its establishment and the start of the New Poor Law era. It is worth noting that it continued to administer relief under Gilbert’s Act until 1852. This case suggests that where Gilbert’s Act had been adopted it had a significant impact on the lives of the vulnerable poor – especially children and the elderly.

Example: the Gilbert’s Parish of Alverstoke, Hampshire, 1799-1834.

The parish of Alverstoke, containing the growing naval town of Gosport, in Hampshire adopted Gilbert’s Act several weeks before the turn of the 19th century. Alverstoke was one of a long line of parishes near the south coast which adopted the Act unilaterally. In Hampshire such parishes included, from west to east, Milton, Milford-on-Sea, Hordle, Boldre, Lymington, Southampton and Bishopstoke. On 9 November 1799, the parish rector, churchwardens, overseers and the inhabitants gathered to consider ‘the propriety of removing the present workhouse of the said parish to a more convenient situation and to find proper employment for the poor’. They all agreed that a workhouse with ‘a new factory to employ them in some Manufacture’ would be beneficial as ‘the profits of which may lessen the expenses of their maintenance and to change the situation of the present poor house to a more convenient one’. Gilbert’s Act, they believed, was ‘sufficient for this purpose’. (56) A committee of gentlemen was then formed to immediately investigate new locations for their new workhouse. (57) A week later they reported that Ever Common would be a suitable location, and applied to the proprietors and owners with shares in the Common for some land. Their application was successful. (58)

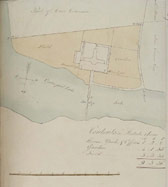

The workhouse was designed with considerable attention to detail. The committee made some preliminary enquires into the general management and successes of other manufactories established within the counties of Hampshire and Surrey. They were furnished with information from the Alton workhouse regarding ‘the manner of employing the poor there – the sort of manufactory carried on – the mode of feeding the Paupers – the Cost of building the House of Industry – the earnings of the people and other information.’ Similarly, the board of the united parishes of Winchester offered some similar details as to how they employed and maintained their poor. It was, however, the information received from the Gilbert’s parish of Farnham which had the biggest impact on the subsequent decisions made by Alverstoke. Farnham had rebuilt their workhouse in 1791, since which date it had received many positive reviews by poor law commentators. The social investigator Sir Fredrick Morton Eden noted in 1797 how their house was built ‘on a good plan, and stands in an excellent situation’ and how mortality rates among the poor had ‘much decreased’ since its construction. (59) Farnham furnished Alverstoke with details of the ‘Cost of the Buildings ground and Workshops with the dimensions’. Thereafter, the Alverstoke committee noted that it was expedient to compose ‘a plan formed on the principles of the Farnham Workhouse together with such improvements as may be thought advantageous’. (60) By July 1800 a final plan of the Alverstoke workhouse was created (see figure 1) and by the following summer it was built – at a cost of £12,000 – and ready to receive its first residents. The workhouse was designed to hold 300 individuals comfortably and had an early panoptical design. (61)

It appears that vulnerable groups were well treated within the workhouse. While it is hard to exactly define ‘care’ or ‘comfort’, there are some indications that the treatment of the elderly and infirm was different to that provided to other workhouse inmates. Indeed, in 1800, the Guardians claimed the elderly and infirm would be ‘comfortably lodged’. (62) When designing the workhouse, for instance, the Alverstoke Guardians planned to build a separate ward for the aged and infirm as well as a detached hospital ward for their further care. (63) The Alverstoke Guardians were determined that these residents should always be provided separate accommodation. The Alverstoke Board first contracted out the maintenance of the poor in 1822. Within the contract between the Board and the contractor(s) was the stipulation that the contractor(s) must ‘reserve as many other rooms as the Visitor and Guardians may consider necessary for the comfort of the aged and infirm’. This suggests that the Board were worried that the rooms they had initially reserved for the elderly and infirm would be converted into work rooms. (64)

The special treatment of the elderly and infirm extended beyond accommodation. During the ‘severe and long’ winter of 1808, the Board decided ‘that the old people were obliged to have fires in their rooms which has caused a greater expenditure of Coals than usual, as this was an unforeseen circumstance the Guardians have been obliged to buy Coals at a high price’. (65) The minutes do not relate that extra coal was provided to other residents, thus the elderly were kept warm regardless of the expense to the parish. The old were also provided with better amounts of, or additional types of, food. The workhouse dietary gave an allowance of tea to all men and women in the house, but the elderly and infirm were allowed extra tea and some sugar. (66) Such a policy was explicitly advocated by Thomas Gilbert. (67) These treats – also called ‘extras’ – were closely monitored in Gilbert’s parishes and unions due to the costs involved. In 1819, an Alverstoke committee examined the possibility of reducing these extras, but it was decided that ‘the indulgence of Tea & Sugar to all such infirm & old Persons shall remain at the discretion of the Visitor and Guardians’. In addition the Medical Officer of the workhouse was to inform the Committee of ‘such Cases as in his Opinion may require the indulgence medicinally’. (68)

Thomas Gilbert expected children, unlike their elderly and infirm counterparts, to eventually leave the workhouse. Educating the young was thought to be a way of preventing them from being a future burden on the poor rates. In Alverstoke a local school was established according to the ‘National system’, and both workhouse girls and boys attended. Here the children were taught reading and writing, and practised sewing and serving. All these activities would, the Board believed, increase the children’s chances of gaining employment in the future. (69) Gilbert’s Act stipulated that the workhouse should only house children until they were ‘of sufficient Age to be put into Service, or bound Apprentice to Husbandry, or some Trade or occupation’. (70) This was adhered to, albeit in an ad hoc manner. Indeed, in 1821 the Board had to remind themselves that they needed to apprentice the boys and arrange situations in service for the girls. (71)

It was thought that religious teaching would reform and maintain good morals among the inmates. The rector would read prayers to the inmates in the house once a week. (72) In other Gilbert’s parishes and unions, for instance, in the parish of Boldre, on the edge of the New Forest, religious instruction was paid particular credence. After the ring of a bell every morning, the inmates gathered to be taught ‘easy and practical’ sections of the New Testament before prayer. Sundays were, perhaps unsurprisingly, almost entirely given over to devotional activities. All inmates sang hymns twice a day. Children, alongside some of the elderly, also attended a Sunday School. (73) Yet such religious instruction did not always result in well-behaved inmates. In Alverstoke in 1820 a few children and several men were accused of breaking into the carpentry shed and stealing the tools. As a consequence, the children were placed in solitary working rooms. (74)

Another major feature of the Gilbert’s Act workhouse was work itself. Many of the inmates at Alverstoke were engaged in domestic employment around the workhouse and in the adjoining garden. (75) Money could only be made, and hence cause a reduction in the costs of welfare provision, through the manufacturing of goods. By 1804 children knitted stockings, made mops and picked oakum. Other residents were ‘employd in a Manufactory of Blankets, Coverlids, flannel, Spinning Mop yarn &c’. Many of these woollen and linen items were actually sold to the house itself, with the rest sold in local markets. (76) While such employment may have fostered habits of industry among the children, the guardians treated inmate’s labour as a source of income which would, at least in theory, reduce the cost of the poor rates. When the Alverstoke guardians assessed the employment of the children in 1806, they noted that the oakum work was still gaining them a ‘profit’. (77)

While the work the inmates undertook was arduous and monotonous, the Board realised some poor residents, and in particular the elderly, were ‘past labour’. (78) The Board seemed to be prepared for this. They had calculated that that roughly one third of the residents in the Farnham, Alton (Hampshire) and Winton (near Bournemouth) workhouses were unable to work and predicted that a larger proportion of their own poor would similarly be unemployable. (79) Even those who were apparently able to work did so inefficiently. In the Easeborne Gilbert’s union it was the inmates’ own ‘unskilfullness’ and ‘want of attention’ that were blamed for the manufactory’s insignificant profits. (80) In 1815 the Alverstoke gentlemen realised that the cause of the manufactory not working well was that no one was strictly superintending it. Furthermore, they thought more profit would come from ‘Sacking and Bagging’ manufacture rather than the making of clothes and bedclothes. (81)

The work regime of the inmates did not change until 1822 when the Alverstoke Board decided to obtain a contractor to take charge of the workhouse. By April 1823 they entered into an agreement with two gentlemen who jointly received 2s 9d for every pauper they maintained per week from the parish. The contractors were to be allowed to keep any profit from the labour of the residents. It was now also the responsibility of the contractor to continue the manufactory as it had stood or instead to implement a new system. (82) Every year the Board assessed the operation of the workhouse and then, if deemed satisfactory, renewed the contract, though sometimes a new contactor was appointed. The weekly rate negotiated between the Board and contractors varied year-on-year. By 1834, the poor were making sacking and picking oakum alongside the usual domestic employments (washing, cleaning, cooking and caring for the ill, elderly and young). (83) The contractors had even received some individuals into the house from nearby Hayling Island. (84) While the Board had to take a step back from decisions surrounding the manufactory and allowing non-settled paupers into the house, they were also anxious to keep their parishioners well maintained. The contracts between the contractor and the Board stipulated that inmates must only undertake tasks which were suited to their ‘strength and capacity’. The Board also laid down maximum working hours. (85) They even reassured the inmates face-to-face ‘that they shall not be oppressed but that they shall have every Comfort and attention their Situation may require’. (86)

Towards a re-examination of Gilbert's Act

This paper has highlighted that regardless of historians’ interest in the workhouse and the welfare of the vulnerable, welfare provision under Gilbert’s Act has been largely neglected. The legacy of the Poor Law Commission has left the impression that Gilbert’s Act was unpopular and thus insignificant. In addition, what we do know about Gilbert’s Act focuses on the politics of implementing the Poor Law Amendment Act and the reluctance of some Gilbert’s unions to dissolution. As a consequence, how the Act impacted on the lives of the poor within Gilbert’s workhouses is largely unknown. Thomas Gilbert created an Act with dual aims: to accommodate the vulnerable and to make the workhouse economically viable by working the poor as much as possible. The examination of Alverstoke shows how the operation of these aims had a significant impact on the lives of the vulnerable poor - they were evidently maintained with shelter, food and warmth and undertook domestic chores and manufactured a variety of products. The inmates appear to have been well cared for, but, in return, the Board expected them to work as much as they could. Education was also an important aspect of life within the workhouse, and was regarded as an investment for the future. The plan was to produce skilled and educated children and then set them up in situations which should, at least in theory, help reduce some future burdens on the poor rates. The inevitable difficulty in implementing a piece of legalisation such as Gilbert’s Act on the ground was that although profits were desirable, there was a risk that the welfare of the inmates would be compromised in its pursuit. The Alverstoke Board managed to juggle these potentially conflicting aims, even showing what thought was compassion towards their poor.

Necessarily, so short a paper exposes as many questions about the legislation as it answers, not least regarding the typicality, or otherwise, of Alverstoke. Whether other Gilbert’s Act boards managed as effectively as Alverstoke clearly needs further investigation. In addition, it remains unclear as to what happened to those groups not central to Gilbert’s policy, namely able-bodied men and women. Were they temporarily lodged within workhouses, provided with outdoor relief or found employment? Alternatively, did boards of guardians lodge the able bodied in the workhouse and thereby seek to profit from their employment therein even though this was prohibited in the Act? When contractors took over the maintenance and employment of the poor in Alverstoke little appears to have changed for the residents. This may have been due to the meticulous planning of the Board to stipulate a number of rules within the contracts which safeguarded the interests of the poor. Whether the residents of other Gilbert’s workhouses experienced such apparently seamless handovers also requires further investigation.

While some research has revealed how stubborn Gilbert’s parishes and unions were in not dissolving in the early years of the New Poor Law, additional questions still need to be asked about how welfare was provided before they were finally abolished. Did the Commission manage to interfere in their welfare regimes, making them adopt principles and policies akin to those implemented in New Poor Law unions? Perhaps hybrid welfare systems developed whereby some aspects of both Gilbert’s Act and the Amendment Act were adopted simultaneously. What made some parishes, such as Alverstoke, finally dissolve before the abolition of the Act is also potentially interesting. Not only will such investigations highlight the bargaining powers of the Commission but they will also reveal the decision-making processes of Gilbert’s Act boards. We know that Alverstoke initially thought Gilbert’s Act met their needs because it permitted them to have an efficient workhouse system. Perhaps a more fundamental question to pose is why other parishes adopted and united under Gilbert’s Act in the first instance. Also, did these intentions differ with those parishes which adopted the Act in different earlier and later years? The exploration of the circumstances surrounding the adoption of Gilbert’s Act will reveal the dynamics of local social policy innovation. Indeed, it could even highlight what ratepayers thought were the best policies to adopt and administer during particular moments, and reveal the personal flourishes they added to policies when they were applied on the ground. Such research will necessarily therefore further our understanding of the treatment, as well as the perceptions, of the vulnerable in the past.

Notes:

- The parish could also ‘farm-out’ the maintenance of their poor to contactors. Back to (1)

- A. Brundage, The English Poor Laws, 1700-1930 (Basingstoke, 2002), p. 12. Back to (2)

- T. Gilbert, ‘Plan for the better relief and employment of the poor; for enforcing and amending the laws respecting houses of correction, and vagrants; and for improving the police of this country. Together will bills intended to be offered to Parliament for those purposes’ (London, 1781), p. 7. Back to (3)

- S. Webb and B. Webb, (English Local Government) English Poor Law History, Part 1, number 7 (London, 1963: 1929), p. 149-313; D. Marshall, The English Poor Law in the Eighteenth Century (London, 1926), especially chapter 3, p. 87-160; P. Slack, The English poor law, 1531-1782 (Cambridge, 1995:1990); M. Rose, The English Poor Law 1780-1930, (Newton Abbott, 1971) p.25-26; S. King, Poverty and welfare in England 1700-1850: A regional perspective (Manchester, 2000), p.24-26; Brundage, The English Poor Laws, p. 10-15, 21-22, 50-51; D. Fraser, The Evolution of the British Welfare State, Third Edition, (Basingstoke, 2003); p.37-38; N. Longmate, The Workhouse: A Social History (London, 2003:1974), p.24-33; B. Harris, The Origins of the British Welfare State: Social Welfare in England and Wales 1800-1945 (Basingstoke, 2004), p. 42. Back to (4)

- A selection of monographs include: M.A. Crowther, The Workhouse System 1834-1929 (Georgia, 1981); Longmate, The Workhouse; S. Fowler, Workhouse: The People, The Places, The Life Behind Doors (Kew, 2007); F. Driver, Power and Pauperism, The Workhouse System 1834-1884 (Cambridge, 1993). Back to (5)

- King, Poverty and welfare, p. 25. Back to (6)

- A. Digby, Pauper Palaces (London, 1978). Back to (7)

- D. Marshall, The English Poor in the Eighteenth Century: a study in social administrative history (London, 1926), p. 159. Back to (8)

- P. Mandler, ‘The making of the New Poor Law redivivus’, Past and Present 117 (1987) 134. Back to (9)

- M. Barker-Read, ‘The Treatment of the Aged Poor in Five Selected West Kent Parishes from Settlement to Speenhamland, 1662-1797’, Ph.D. thesis (Open University, 1988). Back to (10)

- S. Ottaway, The Decline of Life: Old Age in Eighteenth-Century England (Cambridge, 2004), p. 247. Back to (11)

- For example see: A. Hinde and F. Turnbull, ‘The populations of two Hampshire workhouses 1851-1861’, Local Population Studies, 61 (1998), 38-52; N. Goose, ‘Workhouse populations in the mid-nineteenth century: the case of Hertfordshire’, Local Population Studies, 62 (1999) 52-69; D.G. Jackson, ‘Kent workhouse populations in 1881: a study based on the census enumerators’ books’, Local Population Studies, 69 (2002), 51-66; idem., ‘The Medway Union workhouse, 1876-1881: a study based on the admission and discharge registers and the census enumerators’ books’, Local Population Studies, 75 (2005), 11-32. Back to (12)

- P. Thane, Old Age in English History: Past Experiences, Present Issues (Oxford, 2000); Ottaway, The Decline of Life. The latter book mentions Thomas Gilbert’s ideas on pages 57 and 80, and some speculation about the impact of the act on the population of the elderly in the house on page 251. Another example: L. Botelho and P. Thane (eds) Women and Ageing in British Society Since 1500 (Harlow, 2001). Back to (13)

- R. S. Tompson, ‘Gilbert, Thomas (bap. 1720, d. 1798)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, Sept 2004; online edn, Jan 2008. Available: http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/10703; last accessed 10 June 2008]. Back to (14)

- A. W. Coats, ‘Economic thought and poor law policy in the eighteenth century’, The Economic History Review 13 (1960), 46; original information from ‘House of Commons Journals’, XXIX (1764), 737, 850, 899, 946. Back to (15)

- T. Gilbert, ‘A Scheme for the Better Relief and Employment of the Poor’ (London, 1764). Back to (16)

- Coats, ‘Economic thought and poor law policy’, 47; original information from T. Gilbert, ‘Observations upon the Orders and Resolutions of the House of Commons’ (London, 1775). Back to (17)

- As Coats has noted, it is difficult to fully understand the influences which made Gilbert change his opinions of social policies because the House of Commons Committee records relating to the period were destroyed; Coats, ‘Economic thought and poor law policy’, footnote 7, 47. Back to (18)

- T. Gilbert, ‘Plan for the better relief and employment of the poor; for enforcing and amending the laws respecting houses of correction, and vagrants; and for improving the police of this country. Together will bills intended to be offered to Parliament for those purposes’, (London, 1781), p. 3. Back to (19)

- Gilbert, ‘Plan for the better relief and employment of the poor’, p. 6-7. Back to (20)

- Marshall, The English Poor in the Eighteenth Century, p. 160. Back to (21)

- Gilbert, ‘Plan for the better relief and employment of the poor’, p. 11. Back to (22)

- 22. Geo. III c. 83 section XXIX. Back to (23)

- Gilbert, ‘Plan for the better relief and employment of the poor’, p. 7. Back to (24)

- ‘…any poor Person or Persons who shall be able and willing to work, but who cannot get Employment, it shall and may be lawful for the Guardian…to agree for the Labour of such poor Person or Persons, at any Work or Employment suited to his or her Strength and Capacity…and to maintain, or cause such Person or Persons to be properly maintained, lodged, and provided for, until such Employment shall be procured, and during the Time of such Work, and to receive the Money to be earned by such Work or Labour, and apply it in such Maintenance, as far as the same will go, and make up the Deficiency…’, 22. Geo. III c. 83 section XXXII. Back to (25)

- Gilbert, 'Plan for the better relief and employment of the poor', 7 and 22. Geo. III c. 83 section XXXII. Back to (26)

- King, Poverty and Welfare in England, p. 25. Back to (27)

- 22. Geo. III c. 83 section I. Back to (28)

- Gilbert, ‘Observations upon the orders and resolutions of the House of Commons’, p. 3. Back to (29)

- Gilbert, ‘Plan for the better relief and employment of the poor’, p. 9. Back to (30)

- For instance, Richard Burn’s The History of the Poor Laws condemned parish officers for being too harsh towards the poor and fraudulent with the poor rates; R. Burn, The history of the poor laws: with observations, (London, 1764). Back to (31)

- 22. Geo. III c. 83 sections II, VIII and X. Back to (32)

- 22. Geo. III c. 83 sections II and VII. Back to (33)

- Magistrates were required to authorise new Unions and annually review their progress in returns. 22. Geo. III c. 83, section XII states that the returns should include: ‘…where such Poor House shall be situate, make out, or cause to be made out, a just and fair Account of the Expences attending the same, distinguishing them under the several Heads herein specified; and also an Account of the Number of poor Persons, distinguishing their Age and Sex, with shall be contained in every such House at the Time of making such Account, and how they have been employed, and how such Money hath been earned by the Labour of the Poor in the Year preceding…’. As such, these returns are an invaluable source of information, but alas these or draft returns rarely survive. The magistrates’ impact in the welfare process in Gilbert's Unions/Parishes has been little explored. See also 22. Geo. III c. 83 section XXXV. Back to (34)

- 22. Geo. III c. 83 section VIII. Back to (35)

- W. Young, Considerations on the Subject of Poorhouses, (London, 1796), p. 29: cited Webb and Webb, English Poor Law History, Part 1, p. 275. Back to (36)

- Driver, Power and Pauperism, p. 44. Back to (37)

- R. Wells, ‘Review: Bradford Poor Law Union: papers and correspondence with the Poor Law Commission, October 1834 to January 1839’, English Historical Review (2006), 490, p. 237; for instance: Micheldever & East Stratton (Gilbert's Union, Hampshire 1826); Salisbury (Gilbert’s Union, 1821/2); Hursley (Gilbert’s Parish, Hampshire 1829). Back to (38)

- Driver, Power and Pauperism, p.44 and note 45; P[arliamentary] P[aper] 1844 (543.) X. 1. Report from the Select Committee appointed to inquire into the administration of the law for the Relief of the Poor in Unions formed under Act 22 Geo. 3. c. 83 (Gilbert’s Act) [herein abbreviated to: PP 1844 Report from the Select Committee on Gilbert’s Act]; separate return PP 1844 XL Return of Gilbert’s Unions. Back to (39)

- Webb and Webb, English Poor Law History, Part 1, p. 276. Back to (40)

- Driver, Power and Pauperism, p. 44. Driver utilises the returns in PP 1844 Report from the Select Committee on Gilbert’s Unions. Back to (41)

- Longmate, The Workhouse, p. 30. Back to (42)

- Webb and Webb, English Poor Law History, Part 1, p. 275; The Webbs also suggest that the list of Unions formed under the Act provided in the Ninth Annual Report of the Poor Law Commissioners (London, 1843) is ‘incomplete’, and ‘[n]o general description of the working of these is known to us’ apart from in some incidental descriptions in the Annual Poor Law Reports by the requite commissioners, see footnote 1, p. 273. Back to (43)

- Mandler, ‘The Making of the New Poor Law Redivivus’, 133. Back to (44)

- Roger Wells states ‘There is probably more data on the evidentially-obscure post-1782 Gilbert Unions among these papers than anywhere else’; Wells, ‘Review: Bradford Poor Law Union’, p. 233. Back to (45)

- The following website contains a more up-to-date list of Gilbert’s Unions and Parishes [online] The Workhouse Website: www.workhouses.org [last accessed 10 June 2008]. Several adoptions throughout the south and south-west of England have been found by the author. Back to (46)

- Poor Law Commission, First Annual Report of the Poor Law Commissioners for England and Wales (London, 1835) p. 375. Back to (47)

- R. Wells, ‘The Poor Law Commission and publicly-owned housing in the English countryside, 1834-47’, Agricultural History Review, 55 (2007), 193. Back to (48)

- These are the words of Thomas Sockett, Reverend for the Lord at Petworth: S. Haines and L. Lawson, Poor Cottages & Proud Palaces: The life and work of the Reverend Thomas Sockett of Petworth 1777-1759 (Hastings, 2007), p. 169. Back to (49)

- B. Fletcher, ‘The Early Years of the Westhampnett Poor Law Union, 1835-1838’, M.Sc. thesis (University of Southampton, 1981); also see R. Wells, ‘Resistance to the New Poor Law in the rural south’ in J. Rule and R. Wells (eds), Crime, Protest and Popular Politics in Southern England 1740-1850 (Hambledon Press, London, 1997), p. 113. Back to (50)

- A. Brundage, The English Poor Laws, p. 72; Wells, ‘Resistance to the New Poor Law’, p. 113. Back to (51)

- PP 1844 Report from the Select Committee on Gilbert’s Act; the Select Committee continued to collect information in 1845, see PP 1845 (409.) XIII. 1. Report from the Select Committee appointed to consider the same subject in the following Session. Back to (52)

- PP 1844 Report from the Select Committee on Gilbert’s Act, Minutes of Evidence, G. C. Lewis Q. 73, p. 16. Back to (53)

- PP 1844 Report from the Select Committee on Gilbert’s Act, Minutes of Evidence, G. C. Lewis Q. 86, p. 19. Back to (54)

- PP 1844 Report from the Select Committee on Gilbert’s Act, Minutes of Evidence, G. C. Lewis Q. 73, p. 15. Back to (55)

- Understanding the motivations of ratepayers to implement Gilbert’s Act is difficult to decipher from minute books. Although this was the official reason for the adoption of Gilbert’s Act, other motivations - such as to enable them to better care for the vulnerable - may have been considered but were not recorded. Alverstoke’s main reason for adopting the Act may have differed from other parishes and unions which formed under the Act. Such motivations were complicated by the period of time in which the Act was adopted, i.e. the reasons for adoptions in the 1780-90s may have differed from the reasons for adoptions in the 1820s. In addition, parishes may have had a reason for adopting the Act but this does not necessarily mean that their intentions for remaining under Act and their welfare practices under the Act reflected this initial reason. Back to (56)

- Alverstoke Minute Book, 9 November 1799, H[ampshire] R[ecord] O[ffice] PL2/1/1. Back to (57)

- Alverstoke Minute Book, 16 November 1799, HRO PL2/1/1. Back to (58)

- F.M. Eden, The State of the Poor, (3 Vols, London, 1797) i, p. 716-8. Back to (59)

- Alverstoke Minute Book, 26 November 1799, HRO PL2/1/1. Back to (60)

- A more detailed plan of this workhouse can be found in A’Court’s correspondence, ‘Notes on the parishes in the division of Fareham including Portsmouth’, ‘Alverstoke and Gosport’, 21 December 1834, N[ational] A[rchives] MH 32/1. Back to (61)

- Alverstoke Minute Book, 5 May 1800, HRO PL2/1/1. Back to (62)

- Alverstoke Minute Book, 24 February 1800, HRO PL2/1/1. Back to (63)

- Alverstoke Minute Book, 18 December 1822, HRO PL2/1/1. Back to (64)

- Alverstoke Minute Book, 19 April 1808, HRO PL2/1/1. Back to (65)

- Alverstoke Minute Book, 6 August 1818, HRO PL2/1/1. Back to (66)

- In his initial plan, in which he was at odds with parish houses, he noted that the able-bodied would ‘generally consume the best provisions’ at the detriment to the other inmates; Gilbert, ‘Plan for the better relief and employment of the poor’, p. 7. Back to (67)

- Alverstoke Minute Book, 15 January 1819, HRO PL2/1/1. Back to (68)

- Alverstoke Minute Book, Annual Report of 1820, HRO PL2/1/1; apparently 64 boys and 58 girls attended but it is unclear whether this total refers to all the children from the parish attending or just those from the workhouse. By 1834 children were educated by a Schoolmaster employed at £12 per year, see A’Court’s correspondence, ‘Notes on the parishes in the division of Fareham including Portsmouth’, ‘Alverstoke and Gosport’, 21 December 1834, NA MH 32/1. Back to (69)

- 22 Geo III c.83 section XXX. Back to (70)

- Alverstoke Minute Book, Annual Report of 1821, HRO PL2/1/1. Back to (71)

- A’Court’s correspondence, ‘Notes on the parishes in the division of Fareham including Portsmouth’, ‘Alverstoke and Gosport’, 21 December 1834, NA MH 32/1. Back to (72)

- J. Walter, T. Robbins and W. Gilpin, ‘An Account of a New Poor-House Erected in the Parish of Boldre: in New Forest near Lymington’ (London, 1796), p. 19-20. For evidence that Boldre had adopted Gilbert’s Act see: A’Court, ‘Notes on every Parish in the Lymington Division: Boldre’, December 1834, NA MH 32/1. Back to (73)

- Alverstoke Minute Book, Report of 1820, HRO PL2/1/1. Back to (74)

- Alverstoke Minute Book, 8 February 1821, HRO PL2/1/1. Back to (75)

- Alverstoke Minute Book, Annual Report of 1804, HRO PL2/1/1. Back to (76)

- Alverstoke Minute Book, 1 April 1806, HRO PL2/1/1. Back to (77)

- Alverstoke Minute Book, 20 April 1813, HRO PL2/1/1. Back to (78)

- Alverstoke Minute Book, 26 November 1799, HRO PL2/1/1. Back to (79)

- Copies of the yearly accounts of William Bridger, Treasurer of the Easebourne United Parishes (Sussex), Summary of 1798-1799, Petworth House Archives 7869. Back to (80)

- Alverstoke Minute Book, Annual Report of 1815, HRO PL2/1/1. Back to (81)

- Alverstoke Minute Book, 18 December 1822, copy of contract, article 29, HRO PL2/1/1. Back to (82)

- Alverstoke Minute Book, 18 December 1822, copy of contract, article 4, HRO PL2/1/1. Back to (83)

- A’Court’s correspondence, ‘Notes on the parishes in the division of Fareham including Portsmouth’, ‘Alverstoke and Gosport’, 21 December 1834, NA MH 32/1. Back to (84)

- Alverstoke Minute Book, 18 December 1822, copy of contract, article 9, HRO PL2/1/1. Back to (85)

- Alverstoke Minute Book, 1 April 1823, HRO PL2/1/1. Back to (86)