The Imperial War Museum and the history of war

Suzanne Bardgett

The Imperial War Museum was established in 1917 to commemorate the effort and sacrifice of the First World War, at that stage still being fought: one of the first actions of the then curator was to set up a headquarters behind the lines in France and gather detritus from the battlefields – examples of military equipment and uniform which were duly labelled, crated up and sent back to Britain.

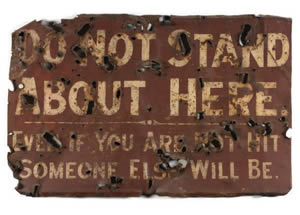

Trench signs

By permission of the Imperial War Museum (IWM FEQ 366 & IWM FEQ 32).

The Museum grew with the momentous events of the 20th century and today covers all conflicts in which British and Commonwealth forces have been involved since 1914. From being a museum primarily concerned until the mid 1970s with the presentation of the operational side of war from the British point of view, it has today evolved into a highly innovative, internationally renowned place where a vast canvas of historical events and themes can be explored, using a rich fund of archival and other sources.

Our exhibition spaces at Lambeth Road have provided several generations of visitors with accounts of Britain's role in the two world wars. For the last 40 years there have been permanent exhibitions of one kind or another detailing the course of each and also providing an insight into civilian life. Today Conflicts since 1945, the Holocaust Exhibition and its sister exhibition Crimes against Humanity, a Victoria Cross and George Cross gallery and our atrium display of large weapons of war complement the core historical narrative displays, ensuring that visitors to the Museum go away having learned quite a lot – ideally a great deal – about how war has impacted on the lives of individuals over the last century.

In addition, there is a long tradition of special exhibitions – interpretations of specific aspects of conflict. It was a stroke of genius, for example, to provide visitors to the newly re-opened Imperial War Museum in 1946 (it had been closed for most of the war and had itself been bombed three times) with Pipeline under the Ocean, which revealed to the public how fuel had been secretly supplied to the continent to support the liberation of Europe just two years before. Three decades later The Real Dad's Army – the first television tie-in exhibition – provided the true story behind the antics of Captain Mainwaring's and Sergeant Wilson's platoon. A format had been established of special exhibitions on mainly social history subjects, which would steadily broaden the Museum's audiences into the 1980s and 1990s.

The opening of the Holocaust Exhibition in 2000 was a major turning point: that the Museum had chosen to deal with this complex and difficult subject in its galleries opened many people's eyes to the breadth of our interests. Today the Museum's exhibitions programme is international in scope, frequently introducing people to unexpected aspects of war – such as Camouflage (2007) or how Ian Fleming's wartime intelligence work informed his novel-writing For Your Eyes Only: Ian Fleming and James Bond (2008).

Our historical exhibitions are intended chiefly to inform people – in an engaging way, exciting in them a curiosity to find out more for themselves and giving them an appreciation of how a museum both preserves and reinterprets the past. The public's reactions are mostly extremely gratifying: 'Amazing, very well organised, rich detail and free' wrote one; another put 'At once brilliant and sobering. A most informative and enjoyable afternoon'.

Art exhibitions have been a constant feature too. The Museum has re-interpreted its own core official art collection in successive decades, mounting retrospectives of particular artists' work. William Scott, Wyndham Lewis, Paul Nash, C. R. W. Nevinson, Eric Ravilious, William Orpen and Henry Moore have all been the subject of such re-evaluations.

Women of Britain – Come into the Factories

Philip Zec, c.1941

By permission of the Imperial War Museum (IWM PST 3645).

From the same department has come also a series of poster exhibitions, themed around particular events, countries or time-frames and providing an insight into how in time of war graphic artists' talents have been used to persuade, cajole, frighten or warn. Towards a New Europe: Visions of the Thousand Year Reich (1985) broke new ground in examining the ideology of the Nazi regime and how it was packaged for the citizens of occupied countries. More recently War Posters: Weapons of Mass Communication (2007) provided a tour de force review of the whole of 20th-century war-related propaganda.

The Museum's collections are vast in their range and depth and are intensively used by numerous different kinds of researcher. Organised according to medium – art, documents, artefacts, film and video, photographs, books, sound records, they are the life-blood of the Museum, providing successive generations of film researchers, authors, academics, radio programme-makers and others with the raw historical material out of which are woven new interpretations of the past.

The fact that so much of what we collect is hard historical evidence – photographs, film, letters and diaries and so on – means that our collections have fed very directly into the public's understanding of the two world wars. Decisions made by our curators on whether to acquire material of course need to be especially well informed – they are creating the archives on which future historians will draw. Many of our curators can look back on careers spanning several decades, – their legacy to have identified and saved for posterity all manner of historical evidence. The fact that we own an example of the aeroplane which dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima, a piece of the Berlin Wall or a headscarf printed to demonstrate support for the Republican cause in the Spanish Civil War is all down to carefully thought-through curatorial decisions.

In addition to exhibitions, publications and website material 'mediated' by the Museum, 'secondary use' by external researchers ensures that our collections are constantly being examined, interpreted and reproduced.

Russian patriotic poster using imagery from the Czarist period as well as communist symbolism.

By permission of the Imperial War Museum (IWM PST 183).

Television provides the most prolifically disseminated example. For over four decades the Museum has provided archival film to researchers working on historical television programmes. The BBC 26-part series The Great War, made in 1964 in association with the Museum, was a landmark project whose approach of archival footage intercut with interviews would remain the 'standard format' for years to come. The World at War – another major production undertaken in association with the Museum – made a longer-lasting impact. It has been broadcast in almost 100 countries and repeated endlessly – one of the most successful television series ever made.

The last three decades of the 20th century proved to be a golden age of British TV documentary-making and the Museum played a key role in this flowering as the principal source of footage for in-depth series such as The Struggle for Poland, The Troubles, The Palestinians and The Cold War.

Radio too has provided an important medium – mainly through documentaries drawing on the Museum's Sound Archive. Radio Four's The Archive Hour and The Last Word frequently draw on our collections. Just last week [20 July 2008] a Radio 3 feature – The Trial of Ezra Pound – used a recording of an anti-Allied broadcast made in 1942 to analyse the accusation of treason made against this controversial poet.

Academic historians and authors of popular history books use our archives intensively – not infrequently as the main staple of their work. Paul Fussell's The Great War and Modern Memory(1) was a seminal work, which drew heavily on the Museum's diverse collection of First World War letters and diaries. The Imperial War Museum Book of series (covering the Western Front,(2) the War in Burma,(3) the War in Italy,(4) and so forth) provided readable and comprehensive insights into what the Museum holds on particular topics. More recently the hugely popular Forgotten Voices series has showcased collections from both the Sound Archive and the Department of Documents. Christopher McKee's Sober Men and True: Sailor Lives in the Royal Navy 1900–1945 was in a similar vein.(5)

Fiction-writers wanting authentic detail will frequently seek our help. Visitors to the Museum's Dome Reading Room have on occasion been distracted by the realisation that Penelope Lively or Sebastian Faulks is there too, researching for a new novel. Len Deighton, Pat Barker, Ian McEwan and William Boyd have also praised the Museum as a source of vital detail for their novels. Actors are similarly drawn to us: Ralph Fiennes used recordings by survivors of Plaszow concentration camp to inform his portrayal of its notorious commandant Amon Goeth in Schindler's List, while Kevin Whately came to research his role as Sergeant Hardy in The English Patient.

Reprinted by permission of The Random House Group Ltd.

In a similar vein, well-remembered examples of famous film directors using our Film Archive for inspiration include Stanley Kubrick for Paths of Glory, John Boorman for his autobiographical feature Hope and Glory and Derek Jarman for War Requiem.

The Museum's imprint on what the public imbibes is thus rather wider and deeper than might at first be imagined.

A final point to mention is that we are, of course, much more than the 'headquarters building' in Lambeth Road. The IWM encompasses HMS Belfast, Duxford Airfield, Imperial War Museum North and the Churchill Museum and Cabinet War Rooms. Each presents a necessarily different perspective on war, but with the Museum's imprint of 'historical narrative backed by collections' clearly to the fore. IWM North's The North at War opened to acclaim in 2005. The Churchill Museum is without doubt the most intensively researched permanent biographical exhibition in London – using state of the art technology to take visitors not only through Churchill's life but the historical events in which he played a major part.

What will the future bring at the IWM? A major forward-planning document entitled 2020 provides a blueprint for what we aspire to be and how we plan to do it. While the massive scale of the two world wars will ensure that they continue to be the major focus for visitors and researchers, the Museum will be building up collections relating to the post-1945 era and mounting exhibitions on themes on that period too.

By permission of the Imperial War Museum.

The needs and interests of ethnic minority groups in Britain need to be better met. From the War to Windrush has recently opened, telling the story of West Indians during the Second World War and beyond. We shall also be doing more to tell the story of communities living in the UK for whom the two world wars are less relevant, but whose memory of, for example, conflict in Bangladesh, Vietnam, Cyprus or Africa is still very fresh.

Most importantly we shall be making sure that we stay relevant, engrossing and trustworthy in how we deliver the history of conflict, growing our collections and expertise to support this far-reaching goal.

- Paul Fussell, The Great War and Modern Memory (Oxford, 1975).

- Malcolm Brown, The Imperial War Museum Book of the Western Front (London, 2004)

- Julian Thompson, The Imperial War Museum Book of the War in Burma 1942–1945 (London, 2004)

- Field Marshal Lord Carver, The Imperial War Museum Book of the War in Italy 1943–1945 (London, 2004)

- Christopher McKee, Sober Men and True: Sailor Lives in the Royal Navy 1900–1945 (Cambridge, Mass., 2002).

Suzanne Bardgett is the Director of the Holocaust Exhibition at the Imperial War Museum.