Research project

Details

The research project 'People in Place: families, households and housing in early modern London, 1550-1720', was funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (ref. RG/AN4417/APN16429) from 2003 to 2006. An additional 'dissemination' grant from AHRC funded work on this website and an illustrated booklet.

The project is a collaboration between Birkbeck, University of London; the Centre for Metropolitan History, Institute of Historical Research, University of London; and the Cambridge Group for the History of Population and Social Structure, University of Cambridge. The project's co-directors are Professor Vanessa Harding (Birkbeck), Professor Matthew Davies (Centre for Metropolitan History), and Professor Richard Smith (Cambridge Group for the History of Population and Social Structure). The research team comprises Dr Mark Merry, Mr Phil Baker, and Ms Gill Newton, with assistance from Ms Olwen Myhill, Administrator at the Centre for Metropolitan History. The project receives administrative support from Birkbeck, the Institute of Historical Research, and the University of Cambridge.

A summary of the grant application, and end-of-year and end-of-project reports to AHRC are available at SAS Space.

Aims

The 'People in Place' project database

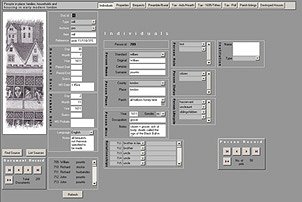

The research project originated in the desire to find a way of charting social change in the early modern metropolis, and the complexities of its social organisation and the dynamics of its 'modernisation'. Several approaches are possible, but an analysis of the family and how it changed over the period promised to provide useful insights. A tenfold increase in population size, and corresponding changes to the population's characteristics, such as their origins, age profile and sex ratios, as well as their skills and job opportunities, must have affected the size and shape of both family and household, and the relationships they encompassed. Likewise, given the changing physical environment, understanding where and how families and households actually lived, what spaces, privacy, and amenities they enjoyed, provides an important cross-bearing on the subject. Tracing changes in the structural characteristics (size, composition, duration, and residential patterns) of the London family and household over a long period, and examining relations within and between households, offers significant new information and understanding.

The project set out, therefore, to develop ways of identifying and tracking over time the changing characteristics of London families and households between c. 1540 and 1710, with the object of using these data as the basis for more qualitative enquiries. In methodological terms, the project's originality lies in integrating two distinct procedures (family reconstitution and property history reconstruction) for the first time, and creating and analysing census-type, cross-sectional data as a means of linking the two. This combined approach multiplies the potential of existing archival, methodological, and technical resources. It has been used to create a substantial database of houses, 'housefuls', households and householders in three contrasting study areas of London in the period c.1540-1710.

Family reconstitution

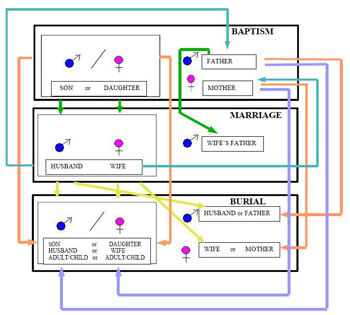

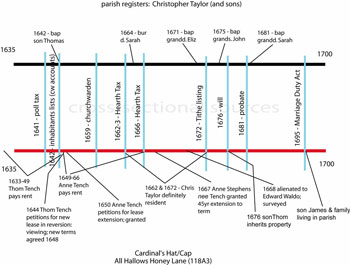

Diagrammatic representation of family reconstitution using parish register data.

Larger image (88KB)

'Family reconstitution' is the short name given to techniques developed by the Cambridge Group for the History of Population and Social Structure for reconstructing population levels and trends using parish register data (baptisms, marriages and burials) for the period from 1538 (when parish registration began in England) to the nineteenth century and the introduction of the decennial census and civil registration. It involves linking series of births, marriages and burials in the same family and comparing the results across thousands of families to derive data on, for instance, nuptiality, fertility, birth parity, and life expectancy, as demonstrated in E.A.Wrigley and R.Schofield, The population history of England, 1538-1851. A reconstruction (1981), and Wrigley, R.S. Davies, J.E. Oeppen, and R.Schofield, English population history from family reconstitution, 1580-1837 (1997).

Similar techniques, with refinements made possible by new technology or necessary by the nature of the material, form part of the approach of 'People in Place'. Reconstitutions of the population of the Cheapside parishes and Clerkenwell are the source for discussions of marriage, fertility and infant mortality.

However, family reconstitution of the traditional kind encounters particular problems in somewhere like London, where people were especially mobile, migratory, and often short-lived. Few Londoners lived for long in one place, and fewer still were born, married and died in the same parish. Many individuals are recorded once only, and the possibility of tracing conjugal families from formation to final dissolution is limited. But it is precisely these characteristics of fragmentation and transience that we need to recapture if we are to understand the London family and household. Careful matching of names is important, and the inclusion of as many kinds of information as possible to confirm and consolidate identities, but there will always be a large proportion of unmatched names.

A key to this project, therefore, is the focus on place. We are not aiming to trace individuals throughout their lives from place to place but to survey the changing population of designated areas at a series of moments in time. We are interested in all the people ever living in our sample parishes, whether they can be directly connected to a biological family or not: foundlings, servants, apprentices, visitors, transients, all formed part of the community, even if fleetingly, and contributed to the complex character of the urban household.

Property history

The reconstitution of families and households is tied to place in another way, in that we seek to locate them in geographical and architectural space by tying them into a series of reconstructed property histories, compiled in the 1980s by an earlier research project, the Social and Economic Study of Medieval London, funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (ref. D/00/23/0044). Although relatively few buildings survive from Tudor and Stuart London, high land values over the centuries have ensured that property-owners created and preserved detailed records of their estates: deeds of title, leases, rent accounts, and memoranda of property management, and, from the seventeenth century, written surveys and estate plans. The city livery companies owned, and in many cases still own, numerous properties in the city, and despite the Great Fire of 1666 and twentieth-century war damage, most of their records survive, as do similar records in the archives of out-of-London institutions such as schools and Oxford and Cambridge colleges. The density of property documentation for the centre of the city is such that the appearance and layout of whole streets of houses can be painstakingly reconstructed. The destruction of property in the Great Fire generated even more documentation, as plots were surveyed prior to rebuilding and disputes over rights settled in court. Comparatively fewer records survive for properties in the suburbs, but at least partial reconstructions are possible, with rich detail for some areas. The Cheapside property histories are available online from British History Online; for an account of the sources, see Keene, Derek, and Harding, Vanessa, A Survey of documentary sources for property holding in London before the Great Fire (London Record Society 22, 1985).

When a family of known size and composition can be 'placed' in a house whose history and description is also known, our understanding of the dynamics of family life is greatly enhanced. It is particularly helpful to be able to tie names of householders in 'cross-sectional' sources, such as tithe or rate lists, or the household listings from the 1695 'Marriage Duty' tax, to properties identifiable on contemporary maps and plans.

Study areas

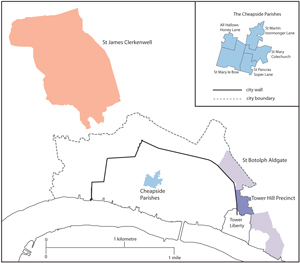

Early modern London's great size, complexity, and diversity effectively preclude a single study of the whole metropolis, and People in Place has proceeded by studying three areas, Cheapside, Aldgate, and Clerkenwell, each with a different developmental history, so that general trends can be distinguished from local characteristics.

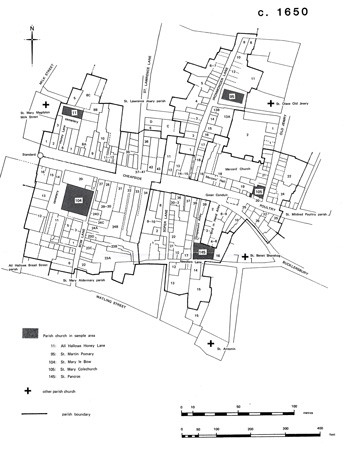

Cheapside. The first area is a group of five city-centre parishes at the eastern end of Cheapside, including the parish of St Mary le Bow, with a combined area of 3 ha. Densely settled from the early middle ages, and with a population of c. 1,200 in 1550, the area was inhabited in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries by retailers and merchants, whose large, comfortably-appointed houses rose to four or five stories. Smaller houses in the side streets housed artisans and craftsmen, especially makers and finishers of the clothing and textiles on sale in the main street shops. The population increased by up to 50 per cent by the time of the Fire. Households were on average large, often with several servants and high-status lodgers. After the Fire of 1666, which swept the whole area, houses were rebuilt on much the same lines as before, and reoccupied by a population of similar character, though at a slightly lower density. Histories of the properties in these five parishes was a keystone of the project's approach.

Aldgate. The parish of St Botolph Aldgate, outside the city wall to the east, was much larger in area (29 ha) than the Cheapside parishes but was only partially built up before the sixteenth century. Part of the parish lay within the city boundary, forming the ward of Portsoken; the larger part lay in the county of Middlesex. Along with London's other inner suburbs, the area experienced enormous early modern population growth, from c. 1,500 in 1540 to at least 11,000 by 1640 and c. 21,000 by 1710. Although there was plenty of open space in 1540, by 1700 it was densely settled. The working population included artisans, labourers, sailors, and those employed in some semi-industrial processes such as soap- and alum-boiling.

Clerkenwell. The parish of St James Clerkenwell lay a kilometre to the northwest of the medieval city, and apart from a cluster of settlement around the church and along some of the roads, most of the 150-ha parish was still under cultivation or husbandry in 1600. Population growth was not rapid till the later seventeenth century, when the number of households nearly trebled from 418 in 1661 to 1,146 in 1708. In 1711 the parishioners estimated the population at 7,200. Clerkenwell housing was still mostly in scattered clusters, with the southern part of the parish more densely settled and the north remaining open; occupations were a mix of the rural/agricultural and the urban, with employment in workshops (clockmaking was a local speciality from the early eighteenth century), labouring and portering, transport, and victualling.

Sources

There is a wealth of historical evidence for family and household in early modern London, ranging from the official - surveys of the population, for example, including returns to the Chantry enquiry in 1548 and the Hearth Taxes of the 1660s and 1670s - to the highly personal, such as the notebooks of the turner Nehemiah Wallington and the private diary of Samuel Pepys.

The Taylor family of All Hallows Honey Lane parish (Cheapside), 1635-1700: a timeline showing the interaction of a wide-range of sources

Larger image (112KB)

Of central importance to this project are the registers of baptisms, marriages and burials, kept by parish clerks from as early as 1538. Despite the Fire, survival of London parish registers has been comparatively good, with significant coverage for the majority of the 130 metropolitan parishes. All five Cheapside parishes are well covered, with registers starting in the 1530s or 1540s and continuing, with some lacunae in the mid-seventeenth century, through the amalgamation of parishes after the Fire and into the eighteenth century. Three of the five have been edited and printed by the Harleian Society (Register Series vols. 44-5, 1914-15). St Botolph Aldgate has multiple volumes of registers from 1558, at times augmented by detailed memoranda by the parish clerk; they have not been edited or published. Clerkenwell registers begin in 1551 and continue through the division of the parish in the early eighteenth century. An edition was printed by the Harleian Society (Register Series vols. 9-10, 13, 17, 19-20, 1884-94). Some parish registers are bare records of events, while others add many details such as age, address, status or occupation, cause of death, and cost of burial. Those that name the parents of children baptised or buried, or of people marrying, are the most valuable for family reconstitution.

A key source for the project is the collection of returns to a tax imposed in 1695, generally known as the 'Marriage Duty' tax. One of several fiscal initiatives to raise money for the wars of the 1690s, it aimed to levy a payment on all marriages, baptisms and burials. Its essential underpinning was a virtual census of the nation's population, collected by parish. Returns for this assessment survive sporadically across the country, but London is well served, with returns for four-fifths of the city parishes. The original returns are in the care of the City of London Records Office; an index to the names in the returns for parishes within the city's walls was published by the London Record Society in 1966 and is available online [link to BHOL 31]. Returns survive for four of the five Cheapside parishes (that for St Pancras Soper Lane is lost), and for St Botolph Aldgate, the latter conveniently divided into precincts. No return survives for Clerkenwell. The depth of detail varies, but most returns list clearly-distinct households, naming adults, children, servants and lodgers or other co-residents. Some, including the return for St Mary le Bow, note occupations. Existing schemes for classifying lists of inhabitants proved unsuited to the complex co-residential patterns which characterise the metropolis, so a new scheme devised by the project team to take account of these was used in analysing household structure in 1695.

No other early-modern population listing offers as much detail as the Marriage Duty tax return, but most listings contribute to building up a picture of local residence, wealth and poverty, occupations, housing character, and more rarely household size. Poll Tax returns from the 1690s were analysed in an earlier Centre for Metropolitan History project, Metropolitan London in the 1690s, which resulted in the publication London in the 1690s: a social atlas, by Craig Spence (2000). The Hearth Tax returns of the 1660s and 1670s, in The National Archive, offer an insight into property size and its variation across London, while a city-wide survey of rents in 1638, made by the church, likewise allows comparison between as well as within parishes. The latter has been published as The inhabitants of London in 1638, ed. T.C. Dale, and is available on London's Past Online; the original returns are in Lambeth Palace Library. Personal taxation (the Tudor and Stuart subsidy) tends to be less informative, since it touched comparatively few people and offers only a general indication of their worth, but local rate lists and surveys, generally found among parish records (in Guildhall Library for the Cheapside and Aldgate parishes; in the London Metropolitan Archive for Clerkenwell), can be very useful. St Mary Colechurch in Cheapside has a remarkable series of pew listings in the seventeenth century, documenting length of residence and movement up the social scale.

Any study of family must make use of wills, recording feelings and relationships as well as bequests to family and friends, and the probate inventories listing personal possessions and household goods. The wills of the wealthiest Londoners, with real property in London and often in other counties, were proved in the Prerogative Court of Canterbury (PCC; originals in TNA). Wills of more modest Londoners, usually with only chattels to dispose of, were proved in the London diocesan courts, the Consistory Court (LMA) and the Archdeaconry and Commissary Courts (GL). By the end of the sixteenth century the City's Court of Husting was no longer a significant probate court. London is not rich in probate inventories (mostly in TNA), but from 1660 the City made and kept inventories of the estates of deceased citizens whose children were under the jurisdiction of the Court of Orphans (CLRO, currently at LMA).

Different kinds of historical evidence survive for the three sample areas. Cheapside has the richest concentration of data, thanks to the value of the properties and the wealth of its inhabitants, so the fullest reconstruction of 'people in place' is possible there. Detailed histories of over 150 properties already exist in the Cheapside Gazetteer, as do a large number of official surveys and taxation assessments, including assessments for the 1695 'Marriage Duty' tax. Parish registers and other sources of nominal data are good enough for a family reconstitution exercise to be carried out. Aldgate is more thinly documented, with much data collected on property but a limited number of completed histories. It has good returns for 1695, however, and a number of surveys that illuminate living conditions in the parish earlier in the seventeenth century. The parish registers survive, but the size of the population precludes a full reconstitution as part of this project. A wide range of data has been collected for Clerkenwell, from rate lists to parish registers, and a full 'family reconstitution' of the population has been completed. Records of property holding, however, have not been used to reconstruct individual property histories in the way they have for the more densely-settled areas.

Further research

The 'People in Place' research team is now engaged on a further study, 'Housing Environments and Health in early modern London', funded by the Wellcome Trust for the History of Medicine, extending the analysis of the three sample areas to include mortality patterns and the topography of disease

The new research project will focus on the correlations between family and household patterns and those of diseases and other causes of death. If we can locate epidemic deaths in particular households or neighbourhoods, we will gain some insight into their incidence and epidemiology, and conversely into the significance of housing quality to general levels of health and disease-resistance. Seasonal variations in mortality are another significant variable. We do not expect to solve the identity of the disease known to contemporaries as plague or pestilence, or the conundrum of its disappearance, but by mapping its impact in fine detail we may be able to make a contribution.