Immigration: saying the unsayable

Eric Homberger, Professor of American Studies, University of East Anglia

A recurrent theme in the experience of social elites in nineteenth-century New York City is the problem of visibility. Anyone aspiring to enhanced social prominence (let's call them social climbers) had to acquire a set of social skills to manage publicity. To be seen in the right places, wearing the right clothes, and in the right company required wealth, discipline, and considerable knowledge of the folkways of the rich. Veritable industries were created to assist the process of social ascent, and to service the consumption patterns which were required by social prominence.

By the 1880s a strikingly modern form of image-management was in widespread use. Central to the process was the New York media, led by the World, Sun, Times, Herald, and Tribune, hungry for celebrity news, scandal and gossip. The press employed 'society journalists' ('Jenny June' [Jane Cunningham Croly] wrote on society for the World in the 1880s) or freelance writers like Harriet Livermore Rice, who sold stories on celebrities to Town Topics and other periodicals. Working with Rice chasing celebrities, socialites, politicians, artists and performers across town was the photographer Jessie Tarbox Beal, newly-arrived in New York and desperate to get her foot in the door, photographically-speaking. (1) The city's formidable social secretaries led by Mrs Astor's Maria de Barril, whose ostrich-feathered hats and dramatic gowns made her something of a New York and Newport celebrity, and Augusta Talltowers in David Graham Phillips's novelette The Social Secretary (1905), and Mrs Carrie Fisher in Edith Wharton's The House of Mirth (1905), who becomes a paid companion, adviser and secretary to the socially ambitious Wellington Brys, suggest how visibility required staff, planning, and social nous. (2) Such figures acted as gatekeepers between the socially ambitious and the press. Interviews, a powerful form of currency, were granted or denied, establishing an approximate rate of exchange between the media and celebrity. (3)

American society was particularly rich in borders, racial, cultural, and ethnic, all the more effective for many being informal, linguistic and tacit. In the case of racial barriers, the system maintained the exclusion of Blacks from employment, accommodation, housing, and religion. 'Quota' exclusion of Catholics and Jews from some Ivy League universities, (4) membership of country clubs, or partnerships in 'White Shoe' law firms, was widespread. America was a deeply prejudiced country, though probably no more so than other advanced industrial societies.

The silent or invisible victims of these multiple forms of discrimination can be suggested by two words: poor immigrants. If the rich sought to exploit visibility, throughout much of the nineteenth century the poor and the immigrants remained an anonymous mass. They were, collectively, those who were acted upon, the recipients of charity, the objects of social control. (5) The immigrant encountered America as a landscape marked by formidable hedgerows requiring increasingly agile navigational skills. The explicit barriers (classically, 'No Irish Need Apply') paled before the implicit ones. Lacking a recognisable 'name' and an identifiable 'family', or anything other than national origin, ethnicity, or religion, the poor - whether native-born or immigrants - remained faceless. (6) They were perceived as a growing and insistent problem, one in which stereotypes, and not individuals, formed the staple of understanding. (7) When Charlotte Erickson wrote of invisible immigrants, she was describing a specific instance of successful adaptation. (8) Most immigrants were visible in the abstract, but highly anonymous as individuals.

The trope of invisibility or facelessness was widely used by reformers when confronting the growing gap between rich and poor in the nineteenth-century city. The poor did not regard the rich as being faceless. You could read about them every day in the newspapers, and from the late 1890s you could see their photographs on the society pages. The poor knew a great deal more about the rich than vice versa. The great social distance between rich and poor, and the high levels of comfortable incomprehension on the part of the well-to-do, posed many problems. In a sermon delivered on 5 June 1836, the Rev. Orville Dewey, a leading figure in the Unitarian church in New York, addressed the widening gap which separated his prosperous parish from the city slums:

If I could take you one walk with me, beneath those over-shadowing tents of poverty, vice and misery; if I could show you how thousands and tens of thousands are living in the very midst of us, though seldom in our sight; if I could open to you all their miserable abodes - from the damp cellar, to the desolate garret - those gloomy tenements, without furniture, without food, without clothing, without one relic of earthly comfort of any sort; if you could see the besotted father, the haggard-looking mother, the loathsome features of sickness and heart-sinking wretchedness, that would glare upon you from many a dismal recess and untended cot; if you could hear the sighings of distress, the mutterings of anger, the sound of imprecations and curses, that measure out the hours of every day you live, and startle the ear of every midnight when you sleep, and which nothing but a strong police can hold in check; and oh! more than all - could you behold poor, pale, forlorn, innocent childhood in those scenes, shivering under reckless threats and blows, more even than from cold and nakedness; children - ah! sacred nurture of parental care, in which yours are reared up - children, unlike yours, trained to vice and beggary by the very first accents of lawful command that they ever hear; trained to falsehood and sin before they ever knew the voice of truth and purity; offered up in all their trusting simplicity a spectacle (God pity it!) to make a heart of adamant bleed-offered up, helpless, innocent victims, upon the altar of their parents' dissoluteness and misery; yes, my friends, if you could see and know all this, you would feel that something must be done in a case so awful and appalling. (9)

Dewey's rhetoric struggles with the problem of social invisibility. 'We' cannot see 'them', though we should. Dewey will give us a simulacrum of seeing through language, a strategy repeated well into the twentieth century: vivid descriptive writing, a form of rhetorical slumming, offered readers a surrogate for first-hand encounters with the tenements and saloons of the city slums. Jacob Riis exploited the technique in How the Other Half Lives. Standing before a tenement, he invited his reader to join him on a visit. 'Suppose we look into one? No. - Cherry Street. Be a little careful, please! The hall is dark and you might stumble over the children pitching pennies back there'. (10) The rhetoric assumes the social divide, and acknowledges the reality of a society strongly riven between 'us' and 'them'.

The many discussions of the poor and immigrants in nineteenth-century America were marked by squeamishness at the language of class. (11) What did the existence of slums and tenements housing hundreds of thousands of New Yorkers, and the presence of so many beggars, mean to those who could not or would not turn away from the spectacle of the city? Urban poverty was blamed upon the poor themselves, due to their foreign origin, or defects of character. James Fenimore Cooper, writing in Paris in the 1820s, believed that misery and abject poverty were rare in New York. Whatever vice and idleness were to be found were caused by conditions elsewhere. The 'poor of Europe', not the American-born, were likely to be responsible. (12) Catherine Maria Sedgwick proclaimed that '[i]n all our widespread country there is very little necessary poverty. In New England none that is not the result of vice or disease'. (13)

The idea that there was a settled class divide was unsayable and un-American, controverting as it did the promise of American individualism, social mobility (14) and the vast cultural legacy of the frontier. Between the 'visible' and the 'invisible' there was a divide which many Americans experienced, but were reluctant to name. The rejection of the language of class was pervasive and deeply entrenched. We can read in the debates over Americanization (15) and the pressure for assimilation a reflection of the problem with no name. Of all the issues which dominated public debate in the 1920s, the question of the immigrant had the most widespread resonance. Wartime propaganda campaigns, and repressive measures, had smashed the German-American immigrant community. Nothing less than '100 per cent Americanism' was now demanded, and the shutters began to be hauled down against immigrants from southern Italy, Sicily, and Eastern Europe. For those already settled in America, the expectation, the demand, was for a rapid move towards full assimilation of American ways. (16) A linkage between sobriety, education and domesticity carried an implicit class meaning, rooted in the values of the middle-class. Be like us, and you will (so the promise went) be one of us. Immigrants could seldom turn away from that pressure; many embraced it with gusto.

The idea of assimilation in the way envisaged by Israel Zangwill in his play The Melting Pot (1908) and in Anne Nicholls' Abie's Irish Rose, which ran on Broadway for five years from 1922, were staples of American popular entertainment in which the idea of turning religious and racial barriers on their heads had impressive appeal. Stanley Kramer's 1967 movie, Guess Who's Coming to Dinner, in which Spencer Tracy and Katharine Hepburn play crusty but lovable parents whose daughter Joanna has just gone and married a handsome and articulate back man (Sidney Poitier) assumed that the audience would be comfortable with Poitier in class terms, which offered a way to approach the more difficult race question. In a popular TV comedy of 1973, Bridget Loves Bernie, an upper-class Irish-American Bridget meets, falls in love, and marries a working-class New York cab-driver, Bernie Steinberg, thus mixing class and religious barriers. Deeply cringe-making stuff.

Nonetheless, the golden dreams of assimilation hovered over the lower East Side. Assimilation meant an escape from poverty, and a move from the ghetto into the affluent suburbs. Assimilation might lead to improved professional and business opportunities, and better chances to provide an education for one's children. While turning their back against tyrannical ideas of compulsory assimilation, the idea of assimilation represented opportunities which most Jews welcomed. The immigrant with his 'allrightnik' approval of all things American is a familiar parody of 'American' values. 'I rushed impetuously out of the cage of my provincialism', gasped the immigrant author Mary Antin, 'and looked eagerly about the brilliant universe'. (17) But the difference, and distance, separating European peasant and the American suburban middle-class was vast, and most of the facile optimism about assimilation lacked persuasiveness. (18)

What has scarcely been considered in this broad cultural discussion is one of the ways that immigrants found to assert control over their own visibility. Photographic studios across the nation produced images of the anonymous millions. (19) These images are not snapshots or 'found' images taken without participation of the subject. Rather, they are the product of a commercial transaction, in which the immigrant and anonymous poor are not 'objects' but become subjects. (20) Within limits imposed by the conventions of the photographic portrait and the technical framework of the modest studio of the professional photographer, such images offer us a way to rethink the general question of visibility and how it is constructed. (21)

In 1910 Jessie Tarbox Beals took a photograph of an immigrant family in a lower East Side tenement in New York City. (22) The family of Italian or Sicilian origin are carefully posed for the occasion. Their small apartment is immaculately clean and tidy, and the five children are dressed for the visit of a photographer to the family home. Mama and Papa (they are not identified by name) live in a grossly-overcrowded apartment, but do not either appeal to the photographer to display their misfortune, or imagine that the public will be moved to empathy at their condition. Rather, there is family pride about this scene, people who are making the best of a difficult situation. In the glass-fronted shelf on the left, where the plates on the top shelf are displayed, there is a lambrequin on which the plates stand. This reminds of Maggie's attempt in Crane's 1893 tale of tenement life to make the Johnson family home a little more refined. 'She spent some of her week's pay in the purchase of flowered cretonne for a lambrequin. She made it with infinite care and hung it to the slightly-careening mantel, over the stove, in the kitchen'. (23) The small detail of the lambrequin is a significant one: with it Mama and Papa express aspiration for their family, which is also seen in the school dress worn by the oldest daughter, the neat shirt and tie worn by the oldest son, and the heavy boots on the boy on the bed on the right. Care, within the family's means, and, hope: that is what Beals' photo contributes to the national debate over immigrants. The stereotypes which pervade How the Other Half Lives by Jacob Riis are implicitly addressed by Beals, and are undermined.

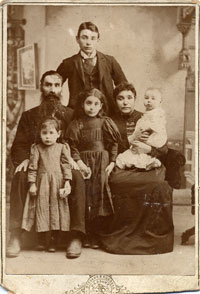

Another image, undated, but likely from the decade before the First World War, was taken in the studio of Stevens & Russell of Pilsbury, Maine. It portrays an immigrant family seated on a sofa before a cloth backdrop painted to suggest a comfortable domestic setting. Everyone is dressed for a special occasion. The setting, arrangement for the camera, and dress tell us things which the family wish to convey: about doing well, looking good, making a success of their new life in America. The family are recent Jewish immigrants, a small part of the great tidalwave of anonymous people who made up what was once described as the 'New Immigration'.

There is pride here, too, in abundance. Coming from the shtetl, knowing little English, Mamele and Papele (they too are unnamed) share the cultural and social isolation of foreigners in a strange land, doubly-foreign in rural Maine, where there was only a tiny Jewish community to welcome them. Thrown more comprehensively upon their own resources than the family in Beals' photo, they nonetheless seek through their children to take the first steps toward assimilation. The oldest son, wearing a fashionable waistcoat and high pointed collar, looks at the photographer with a confidence lacking in the youngest daughter standing uncomfortably between Papele's big brogues. The facial expressions of Papele and Mamele are essentially the same expression, one of resignation. There is little to expect for them now, but much that might be possible for the children.

The oldest boy will do well, and go far. Without misgivings, he will Americanize his family name, and work in the big world where immigrant Jews are unknown. The parents in both images may never quite become comfortable speaking English, and their knowledge of American customs and history is sketchy, but they are, to an extent, adapting to the new world. Immigration provided a way of escape; there was pride in the old ways, and a devotion to Sabbath ritual and reading the Yiddish-language Forverts; but not enough to temper their fierce secular aspiration for the children's self-fulfilment.

The photographs show two immigrant families conforming to many American values. They are evidence of the power of those values and stereotypes, and of the way they were internalised and reproduced within immigrants who may have had only the most glancing and marginal knowledge of American life. The face these families present to the camera, and to the land where they have settled, is not without ambiguities and conflicts. The parents in both photographs do not expect their daughters to gain an education, and that will be a source of deep resentment and frustration, turning the kitchen table into an on-going battlefield. But it is their faces, arranged to suit their aspirations, which makes visible what society had largely preferred to think about in terms of an anonymous mass. Photography made it possible for the first time to see the anonymous, and watch them take responsibility for their own visibility.

Notes:

- Alexander Alland, Sr., Jessie Tarbox Beals: First Woman News Photographer (New York: Camera Graphic Press, 1978), pp.56-58. Back to (1)

- Jerry Patterson, The First Four Hundred: Mrs. Astor's New York in the Gilded Age (New York, 2000), pp.40-1. Back to (2)

- Eric Homberger, Mrs Astor's New York: Money and Social Power in a Gilded Age (New Haven and London, 2002), pp.1-34. Back to (3)

- In 1922 the president of Harvard, A. Lawrence Lowell, proposed a quota (15 per cent) on the number of Jews admitted to the university. Lowell was convinced that Harvard could only survive if the majority of its students came from old American stock. The quotas remained until loosened and then abolished in the late 1930s. Similar concerns were expressed, if not acted upon, in the 1990s in response to the spectacular academic performance of Asian-American immigrants, and their children. Back to (4)

- This is the argument in Eric Homberger, Scenes from the Life of a City: Corruption and Conscience in Old New York (New Haven and London, 1994), pp.10-85. Back to (5)

- An extraordinary instance of the virulence towards the anonymous poor is 'Poor-Laws and the Sources of Poverty Among Us,' New York Quarterly, (January 1854), 2: 581-605. Back to (6)

- A strategy adopted by defenders of immigrants would seek to put a human face upon the anonymous masses. Opponents of immigration were ruthless in insisting upon the threatening faceless. These rhetorical possibilities were clearly employed in the recent British debate on the stereotyped 'Polish plumber' and other immigrants from the new accession states to the EU. Back to (7)

- Charlotte Erickson, Invisible Immigrants. The Adaptation of English and Scottish Emigrants in Nineteenth-Century America (Leicester, 1972). What Erickson meant by 'invisible' was a marker of successful assimilation. The emigrants she discusses managed to make themselves invisible through an adaptation in America to what were essentially familiar folkways to immigrants from the British Isles. Back to (8)

- Rev. Orville S. Dewey, A Sermon Preached in the Second Unitarian Church in Mercer-Street, on the Moral Importance of Cities and the Moral Means for their Reformation, particularly on a Ministry for the Poor in Cities (New York, 1836). On Dewey see Walter Donald Kring, Liberals Among the Orthodox: Unitarian Beginnings in New York City 1819-1839 (Boston, 1974). Back to (9)

- Jacob Riis, How the Other Half Lives, ed. Donald N. Bigelow (New York, 1957), 33. Back to (10)

- The exceptions are well-known (see Sean Wilentz, Chants Democratic: New York City and the Rise of the American Working Class 1788-1850 [New York, 1985]), but they remain isolated voices in the broader culture of the United States. See on this the work of Gareth Stedman Jones, Outcast London: A Study of the Relationship Between Classes in Victorian Society (Oxford, 1971), and Languages of Class; Studies in English Working Class History, 1832-1982 (Cambridge, 1983). The 'classic' sociological approach to class is analysed in Milton Gordon, Social Class in American Society (Durham, 1958). More recent scholarship suggests that class has been absorbed within a different set of analytic categories: Karen E. Rosenblum and Toni-Michelle C. Travis, The Meaning of Difference: American Constructions of Race, Sex and Gender, Social Class and Sexual Orientation (New York, 1996). Back to (11)

- James Fenimore Cooper, Notions of the Americans Picked Up by a Travelling Bachelor, with an Introduction by Robert E. Spiller, 2 vols. (New York, 1963), pp.1, 142-3. Back to (12)

- Catherine Maria Sedgwick, The Poor Rich Man and the Rich Poor Man (New York, 1837), p.22. Late nineteenth century writing is more sensitive to the growing class divide. See Christopher P. Wilson, White Collar Fictions: Class and Social Representation in American Literature, 1885-1925 (Athens, GA, 1982), and Elsa Nettels, Language, Race and Social Class in Howells's America (Lexington, 1988). Back to (13)

- Eric H. Monkkonen puts it this way about nineteenth-century urban populations: '...every city lost about half of its inhabitants every decade' in America Becomes Urban: The Development of U.S, Cities & Towns 1780-1980 (Berkeley, 1988), 195. Those who remained part of the stable 'visible' population prospered, the 'invisible' transients were likely to be poor and rootless. Back to (14)

- 'Broadly speaking, we mean [by Americanization] an appreciation of the institutions of this country, absolute forgetfulness of all obligations or connections with other countries because of descent or birth' - Superintendent of the New York Public Schools, New York Evening Post, August 9, 1918. Quoted by Isaac Baer Berkson, Theories of Americanization: A Critical Study, with special reference to the Jewish Group (New York, 1920), ch. 2. Back to (15)

- Angela M. Blake, How New York Became American 1890-1924 (Baltimore, 2006). Back to (16)

- Mary Antin, The Promised Land (Boston, 1912), p.181. Back to (17)

- See, for example, Robert E. Park and Herbert A. Miller, Old World Traits Transplanted (New York, 1921). The sociologist W.I. Thomas was arrested in 1918 by agents of the FBI on the charge of having violated the Mann Act (crossing state lines for immoral purposes, and for false hotel registration). The case was thrown out of court, but Thomas, without protest from his colleagues, was dismissed from the University of Chicago. He never again held a regular university post. Old World Traits Transplanted was published in 1921 under the false name 'Herbert A. Miller'. Back to (18)

- Martha A. Sandweiss ed., Photography in the Nineteenth-Century (Fort Worth and New York, 1991). Back to (19)

- The approach suggested appears in Eric Homberger, 'J.P. Morgan's Nose: Photographer and Subject in American Portrait Photography', in The Portrait in Photography ed. Graham Clarke (London, 1992), 115-131. Back to (20)

- Photography was part of the apparatus of surveillance created in the nineteenth century in response to the perceived social threat of the 'invisible'. See on this Foucault, passim, and John Tagg, The Burden of Representation: Essays on Photographies and Histories (Basingstoke, 1988). Back to (21)

- This photo is reproduced as plate 39 in Alland's pioneering Jessie Tarbox Beals (note 1), but the plate from the Museum of the City of New York has been strangely cropped, eliminating the two older children on the left side of the photo. Back to (22)

- Stephen Crane, 'Maggie: A Girl of the Streets' in Prose and Poetry, ed. J.C. Levenson (New York, 1984), p.28. Back to (23)