articles > Cold War and the periphery...

Cold War and the periphery

John Kent, London School of Economics

The origins of the Cold War are often placed in Europe by orthodox historians and so ignore its global origins as well as the issue of whether the Cold War's development was driven by European events.

The precise nature of the Cold War – a war fought by all means short of international armed conflict (1) – was soon defined by policy makers, and had an important bearing on its subsequent interpretation. The idea of the Cold War as a realist extension of inter-state relations (2) and therefore concerned with hard power, Soviet-American diplomacy and foreign policy, underestimates the importance of ideology and the role of covert operations and propaganda. These were central to this war that involved everything but international armed conflict, and have defined the debate on whether the Cold War was more a war of ideas and soft power rather than a war dominated by the importance of nuclear weapons and military strength. In addition, the fact that such a war allegedly developed into one in which non-European areas became more important reflected the questionable idea of a spread from Europe to the periphery. In reality the Cold War originated because of global, not European, problems. The non-European areas became more important in the Cold War and by the 1960s many peripheral areas of the less developed world had assumed central significance. (3) This reflected the fact that the ideological elements, which focused on the competing socio-economic systems and the political forms they produced, became a more direct concern of policy makers fighting the Cold War.

At the end of the Second World War the Big Three allied powers failed to reach agreement on the peace treaties but also on the nature of the post-war international order and the global distribution of power. (4) These issues were certainly dominated by questions of power and prestige and can be traced to such concepts as spheres of influence and territorial disputes of a global nature. Asia, the Middle East and the Pacific have not been given the importance that they deserved in analyses of the increasing tension in 1945–6. Europe, the original source of conflict, was simply the most important area to control because it provided the main source of military manpower and economic strength. The idea that Soviet dominance over its eastern parts should be accepted by the Western allies was rejected. Yet Britain and the United States remained determined to retain dominance over areas of the globe in Asia, Africa and Latin America under the now changing forms of imperialism and the impending end of colonialism. The tensions that developed particularly in 1945 at the Potsdam summit and the first Council of Foreign Ministers reflected the failure to agree on the nature of a new global order involving the United Nations and the incorporation of great power influence and control to be exercised in Europe, Asia, Latin America and Africa. This produced the western measures culminating in the Marshall Plan to contain the Soviet Union and maintain capitalist democracy in Europe. (5) In other words Cold War tensions began because of a global conflict in which Europe was the driving force not as a conflict over Europe that spread to other areas of the globe.

The nature of global power and the new international order reflecting the hard power in Europe were then overtaken by events in the periphery once the Cold War assumed a clearly defined form (a war fought by all means short of international conflict) by 1950. Traditional or orthodox interpretations see the success of the communists in the civil war China in 1949, followed immediately by the civil war in Korea (6) and accompanied by the civil wars in Malaya and Indochina, as the spread of the Cold War. Yet it is more accurate to see it not as the globalisation of the Cold War but as the Cold War becoming less concerned with hard power and more concerned with ideology and soft power in which events in the periphery were more important. This essentially coincided with the end of the initial phase of western containment in 1948 (7) and the West's use of psychological warfare and propaganda to fight a more offensive Cold War. This was soon affected by the need to prevent hot war given the destructive power revealed with the explosion of hydrogen bombs in 1953.

This increasingly important requirement culminated in the Cuban Missile Crisis when the end of the French and British empires were transforming the world and making many peripheral areas crucial to the Cold War conflict. With Eastern Europe still dominated by the Soviet economic and political system, despite Stalin's death in 1953, and with capitalist democracy preserved in the West, the stabilisation of Europe seemed complete. The issue by the end of the fifties was whether the newly independent states that were emerging would become part of the western capitalist world or follow the example of Cuba. This battle for hearts and minds was at the centre of the Cold War and the periphery's importance. The non-aligned movement was connected to the struggle of non-European people for independence and it was the ideological battle over democracy and capitalism that remained crucial in the development of the Cold War.

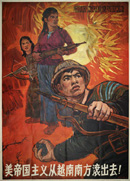

The ideas of the Cuban Revolution had momentous significance for much of the world as the costs and benefits for non-European peoples were highlighted in economic and political terms by the end of colonialism. Consequently ideology assumed even more importance for the people of the emerging newly independent states. The conflicts in Portuguese Africa and the Congo were followed by the increased American involvement in Vietnam that drove the Cold War forward. (8) Even though at the start of the 1970s détente defined the latest attempts to improve Soviet-American relations and prevent a major hot war, the Cold War was still being fought. This battle for hearts and minds and the propaganda and covert operations to influence socio-economic change in the non-European world continued with brutal assassinations to gain political control. These gruesome manifestations of the Cold War produced by ideology were most evident in the periphery, and détente's collapse was clearly connected to events in the less developed world.

The end of the Cold War in 1988–9 was also dominated by ideology, even if its impact was now felt most in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union. (9) This was after exactly four decades during which the global conflict that the Cold War had always been after 1945 had centred on areas of the world outside Europe. From 1948, when it became clearer that the Cold War was essentially an ideological conflict, the periphery replaced Europe as the central focus of that conflict. Only with the events that produced the end of the Cold War did Europe re-emerge as the driving force of the global struggle.

Notes:

- This definition from the British military fitted the interpretation and of western policy in the 1950s. Back to (1)

- For realist interpretations see from a historical perspective, see H. Jones and R. B. Woods, Dawning of the Cold War: the US Quest for Order (Athens, Ga., 1991); and for the issue of power, see M. Leffler, A Preponderance of Power: National Security, the Truman Administration and the Cold War (Stanford, Calif., 1992). Back to (2)

- For an introduction to the non-European world and the Cold War at the start of the sixties see John W. Young and John Kent, International Relations since 1945: A Global History (Oxford, 2004), pp. 160–3, 165–70. Back to (3)

- For details see Leffler, A Preponderance of Power, chap. 1; P. Dawson Ward, The Threat of Peace: James F. Byrnes and the Council of Foreign Ministers 1945–46 (Kent, OH, 1979); J. Kent, British Imperial Strategy and the Origins of the Cold War 1944–49 (Leicester, 1993), pp. 76–116. Back to (4)

- M. Hogan, The Marshall Plan: America, Britain and the Reconstruction of Western Europe 1947–52 (Cambridge, 1987). Back to (5)

- The Korean War began as a civil war (i.e. the Cold War) but became an international armed conflict with Chinese troops attacking American forces (a hot war). Back to (6)

- This argument is put in Young and Kent, International Relations, pp. 121–26. Back to (7)

- Of the numerous books on Vietnam see especially F. Logevall, Choosing War: the Lost Chance for Peace and the Escalation of War in Vietnam (Berkeley, Calif., 1999) and David Kaiser, American Tragedy: Kennedy, Johnson, and the Origins of the Vietnam War

(Cambridge, Mass., 2000).

Back to (8) - Mark Kramer, 'The collapse of the Soviet Union', pts I and II, Journal of Cold War Studies, 5,1 and 4 (2003); Mark Kramer 'The collapse of East European communism and the repercussions within the Soviet Union', pts I, II and III, Journal of Cold War Studies, 5, 4 (2003), 6, 4 (2004), 7, 1 (2005). Back to (9)