The treasure roll

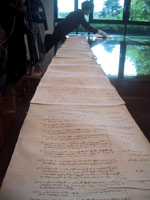

The treasure roll describes the jewels and plate belonging to King Richard II (reigned 1377-99), and to his two queens, Anne of Bohemia and Isabelle of France. The inventory dates from 1398 or 1399, the period of Richard's tyranny. It contains 1,206 entries, some describing dozens of pieces, and is written on forty long, narrow parchment sheets known as membranes (abbreviated as m. for one membrane, or mm. for two or more). Fully unrolled it measures more than 28 metres.

The treasure roll partly unrolled (Kew, The National Archives)

The roll was rediscovered in the 1990s in the National Archives at Kew, and is a very rare survival from later medieval England. It is now catalogued among the records of the Exchequer, where it has the reference TNA: PRO, E 101/411/9 (see The National Archives website). French was still spoken and written at the English court in the late fourteenth century. Many records of this date, including the treasure roll, are written in French. Others are in Latin and a few in English.

From the time of King Edward III in 1340 until the Tudor period, English kings reserved the right to keep secret the expenditure of the Chamber (their personal accounting department). The records of Parliament suggest that this roll may have come into the central records of the crown after Richard's deposition because it was needed in 1401 for a survey of his treasure under his usurper, Henry IV (1399-1413).

Every object listed is of precious metal or of materials such as beryl, rock-crystal, coconut, amber, ivory and jet mounted in gold or silver. Almost all are given a weight and value. (For a guide to the weights and values used in the roll, see the weights and coinage pages.) The total adds up to the staggering sum of well over £209,000. Around 1400 the wages of a master craftsman might be 6d. per day, so that forty days work would be needed to earn the equivalent of one pound.

The objects in the inventory are divided by metal type and by function. First come gold objects for secular use, then those of silver-gilt and silver. The headings for the gold objects are crowns, gold vessels (these being mainly for the table), chaplets, circlets and collars, 'ouches' meaning brooches, 'hanaps' meaning cups, some paired with ewers, and finally a section of very miscellaneous small jewels.

Silver-gilt objects of all different types are listed together, but a special section is reserved for the vessels in use in the king's household. This section ends with many pieces seized from the magnates known as the Lords Appellant whom Richard executed or exiled as traitors in 1397.

The chapel goods follow, divided in the same way. By far the largest number are gold, some are silver-gilt and only a few silver.

Besides pieces inherited by Richard or given to him by his courtiers and as diplomatic gifts, the inventory contains jewels and plate from Isabelle's trousseau and many forfeited goods. The only piece known to survive today is a crown later given to Henry IV's daughter, Blanche (see crowns).

Inventories of valuables are one of our best sources of information about princely collections and about the appearance and techniques of lost medieval objects. Jewels and gold and silver vessels which once belonged to kings and princes or to other secular magnates only very rarely survive. This is because objects of precious metal were often treated as bullion and used for payment instead of coin or alternatively were melted down and remade when they were thought to be old and out of fashion. Most medieval valuables known today were preserved in the treasuries of churches and religious houses in continental Europe. In England the Reformation under Henry VIII and the Commonwealth under Oliver Cromwell meant that there were disastrous losses.