On stage

William Shakespeare's play Richard II was first performed in 1595 by the Lord Chamberlain's Men, the company of actors for whom Shakespeare was the regular writer and who, in the mid 1590s, became the favoured performers at the court of Elizabeth I.

The plot centres on the king's forced abdication in favour of his Lancastrian cousin Henry Bolingbroke. Bolingbroke, the son of John of Gaunt and grandson, like Richard, of Edward III, is presented as altogether more manly than Richard, whose personal weakness is shown in stark contrast to his regal power. The need for a monarch to display a strength of character equal to his royal authority was a highly appropriate message for Elizabethan audiences, and Shakespeare's history is adjusted to suit a distinctively Elizabethan point of view. Elizabeth I had constructed for her subjects an image of herself in which her own personality – indefatigable, determined, devoted to her people and country – had come to contain and represent the abstract qualities required of the good monarch. However, her failure to produce an heir made a play about deposing a monarch politically sensitive, and the first three editions of Richard II were all censored to remove the abdication scene.

A playbill for Edmund Keane's third performance of Richard II, from 1815. (By permission of the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust.)

The desire of theatre directors and designers to maintain strict historical accuracy has not always been any greater than Shakespeare's own. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries it was not uncommon for the texts of his plays to be altered to suit the taste of contemporary audiences. The playbill for Edmund Keane's third performance of Richard II at the Theatre Royal in Drury Lane in 1815, for example, promises 'considerable alternatives and additions from the writings of the same author'.

An engraving of William Charles Macready (1793-1873) as Richard II. (By permission of the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust.)

Designs, too, reflected the style of the day. Macready's version of the king, shown in this engraving of 1850, clearly owes a great deal to the mid nineteenth-century Gothic revival, as can be seen from the table and chair at which the deposed Richard broods.

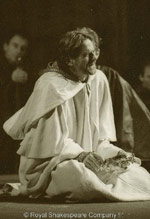

In the RSC's 1964 Stratford production, David Warner's Richard is dressed in a manner which more clearly copies details from visual sources of the late fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries. His trumpet-bell collar recalls that of the robe of Ilaria del Carretto on her tomb in the cathedral of Lucca in Tuscany dating from around 1406 and he is seated on a throne reminiscent of the Coronation Chair in Westminster Abbey. His crown is of a type similar to that worn by Richard himself in the Westminster Portrait of c.1395. The eight fleuronsfleurons - lily-shaped pinnacles , alternately large and small, are set above a tooled gold band set with balas rubiesbalas rubies - rose-red variety of spinel ruby .

David Warner as Richard II. (Reg Wilson © Royal Shakespeare Company.)

The lily-shaped pinnacles or fleurons rising from the circlet of Warner's crown alternate in size. In the heavily-restored Westminster Portrait the disparity between their sizes is much less and in this respect the RSC design bears more relation to the crowns of Saints Edmund and Edward the Confessor in the Wilton Diptych.

The 1987 production, in which Jeremy Irons played the king, also attempted a kind of quasi-medieval realism, although the crown which Richard is renouncing in the photograph is simpler still than David Warner's. It comprises a gold circlet with small, jewelled fleurons of consistent height, each rising above a single gem set into the band. It may derive from a type known from some surviving fourteenth-century crowns associated with the Hungarian kingdom. A similar 'little crown' in the inventory is so light that it might have been intended for a reliquary figure or statue.

Jeremy Irons as Richard II. (Reg Wilson © Royal Shakespeare Company.)

One distinctive feature of many crowns of the fourteenth century which is seldom, if ever, reflected in theatre designs is their hinged construction. The inventory of Louis I, duke of Anjou and the brother of Charles V of France, states that all his circlets were hinged and the word 'overages', used of most of the crowns in Richard II's inventory, indicates that these too were composed of linked sections rather than a seamless circle of gold. One of the crowns described in the inventory still survives today in Munich (see crowns). It is constructed like this, with removable fleurons and a circlet that could be laid flat for transport. Ease of handling, however, is crucial to any theatrical prop and as the photographs show, the needs of the production have usually won over accurate period detail.

J.H.