Resources

Books

Web Sites

Reviews and

Articles

Research

Reviews: Empire

Imperial history

was long viewed as merely a variety of British history, thanks

to Sir John Seeley's 1883 Expansion of England, in which he

projected the evolution of its empire as 'the great fact of

modern English history', reflecting Britain's contemporary

imperial apogee. However, in the century that has elapsed since

that heyday, decolonisation and economic and political globalisation

have recast imperial history as the history of empire(s), while

histories of colonialism have sought to provide a counterpoint

to the 'top down' emphasis of old-style imperial narratives.

As Elizabeth Buettner writes of Britain in her review of Catherine

Hall's edited volume, Cultures

of Empire: Colonizers in Britain and the Empire in the Nineteenth

and Twentieth Centuries: A Reader (MUP, 2000), 'It is now

increasingly common to assert that empire was crucial to the

identity of colonizers as well as colonized, that Britain's

domestic and overseas histories cannot be disentangled, and

that imperial dimensions continue to be relevant in Britain

as well as former colonies in the wake of widescale decolonization

after the Second World War.' Indeed, as Robert Harris observes,

in considering the late Philip Lawson's collected essays in

A Taste for Empire

and Glory: Studies in British Overseas Expansion, 1660-1800

(Ashgate, 1997), 'The new history of empire is a history

of representation as well as of administration, politics, trade

and war. It is also a history that forces the historian to

cross boundaries between countries within as well as beyond

the British Isles.'

Accidental empires?

Seeley was perhaps less celebratory of British

imperial achievement than his reputation allows; he did for

example acknowledge the haphazardness of imperial expansion,

in observing 'We seem . to have conquered and peopled half

the world in a fit of absence of mind'. Indeed, modern histories

of imperialism have explored the uncertainty and instability

behind overseas expansion with enthusiasm; for example, Bruce

Lenman's England's

Colonial Wars 1550-1688/ Britain's Colonial Wars 1688-1783

(Longman, 2001) stress, as Peter J. Marshall notes in his

review that 'the outcome of England's and Britain's colonial

wars was never predictable and their consequences were rarely

what contemporaries intended.' Lenman, in his response, goes

further still: the 'whole assumption that official British

culture in the period 1688-1783 was stamped by a particularly

imperialistic outlook is itself very dubious'.

This historiographic turn away from intentional

imperialism is very marked in the field of late nineteenth-century

European colonial endeavour, which is now more often studied

through the lens of domestic politics, than it is considered

as a globalising phenomenon. The thesis of Amanda Sackur's

and Tony Chafer's edited volume, Promoting

the Colonial Idea: Propaganda and Visions of Empire in France

(Palgrave, 2001) is, William Gervase Clarence-Smith contends,

'that empire was more theatre than substance for the West.

Expansion overseas was principally a way to paper over internal

cracks in the political and social fabric of industrialised

nation states' . A similar view is presented in Matthew Seligmann's

Rivalry in

Southern Africa: The Transformation of German Colonial Policy

(1998), reviewed by Annika Mombauer, who rehearses the

observation of the German politician, Bernhard von Bülow:

'the question is not whether we want to colonize or not, but

that we must colonize whether we want to or not'

Governing empires

Whether or not colonial territories have been

intentionally or accidentally acquired, imperial government

has also been subject to reexamination by 'new' historians

of empire. The ambivalent status of commercial companies like

the East India Company and its Dutch counterpart, the VOC in

the territories where they operated, has been subject to extensive

study; one of the more unusual investigations has been that

of Richard Grove, in his

Green Imperialism : Colonial Expansion , Tropical Island Edens

and the Origins of Environmentalism , 1600-1860 (CUP, 1996),

which Bill Luckin feels ably shows how 'the politics of environmental

exchange [throw] revealing light on larger social and political

issues - not least the highly complex and ambiguous status,

in relation to formal state structures, of the Dutch and English

East India Companies.'

Government in British India increasingly depended

upon military enforcement, underlining what Ian Beckett, in

his review of David Killingray and David Omissi, eds., Guardians

of Empire: The Armed Forces of the Colonial Powers, c.1700-1964

(MUP, 1999) calls 'the necessity of military power as the

basis for empire'. Beckett also praises Killingray and his

contributors for pointing up two further military consequences

of empire - the 'degree of collaboration ... upon the part

of indigenous recruits' who were 'cheaper' to sustain and less

expensive than domestic troops to lose; and, perhaps dependent

upon this last factor, the 'increasing role of colonial manpower

in the world wars of the twentieth century'.

The tension between imperial endeavour and

government, and nationalist aspirations is highlighted by Geoffrey

Hosking, in his Russia:

People and Empire 1552-1917 (Harper Collins, 1997); as

Peter Gatrell acknowledges in his review, 'In the process of

creating an empire, the existing institutions of community

that might otherwise have provided the basis for a "civic

sense of nationhood" were weakened and crushed.'. By contrast,

British urbanisation in the eighteenth century appears to have

been positively framed by imperial pursuits and administrative

and commercial agendas: Sarah Richardson, in her review of

Kathleen Wilson, The

Sense of the People: Politics, Culture and Imperialism in England

1715-1785 (CUP, 1995), a study of urban politics and opposition

in Newcastle and Norwich, summarises 'Trade, empire and war

supported the political and cultural infrastructure of the

urban renaissance.'

Two works also attest to the problems engendered

by colonial governance - both military and civilian - back

in the 'homeland'. In discussing Sebastian Balfour's Deadly

Embrace: Morocco and the Road to the Spanish Civil War (OUP,

2002), which considers the role of Spanish troops in the

government of its hardwon Moroccan territories, Francisco J.

Romero Salvadó praises Balfour for providing 'a valid

model with which to understand the mentality and ideology of

the colonial corps and its potentially destabilising role when

confronted by metropolitan administrations.' Similarly disruptive

consequences, which Robert Harris sums up as 'the corrupting

effects of empire' are explored in Philip Lawson's explorations

of what Harris terms the 'rapacity and greed of servants of

the East India Company' and the impact upon the eighteenth

century British polity.

Economics of empire

The economic history of empires may be less

fashionable than more culturally-framed approaches, but that

has not stopped Niall Ferguson erecting a new history of how

'Britain made the modern world' on a superstructure of what

he terms economic 'anglobalisation', rather than upon issues

of exploitation, acculturation and oppression. Andrew Porter,

in his review of Ferguson's book and television series, Empire

(Penguin/ Channel 4, 2002/2003) with its emphasis upon

Britain's unprecedented role in the 'optimal allocation of

labour, capital and goods in the world' - is highly critical

of what he sees as a retrograde development, back towards a

Whiggish history of empire.

One of the areas which Porter sees Ferguson as neglecting is

the complexity of imperial infrastructures like slavery. As

David Richardson remarks in his review of Kenneth Morgan's

Slavery,

Atlantic Trade and the British Economy, 1660-1800 (CUP, 2000),

'The relationship between slavery, colonialism, capital accumulation

and economic development has long been an issue that has exercised

political economists and economic historians' . These are far

from static debates, as continued attention to the issue of

Britain's unique industrialisation in the eighteenth and early

nineteenth centuries and the role of slavery in that industrialisation,

witnesses. Richardson is indeed critical of Morgan's failure

to explore this in more critical detail, especially since he

does acknowledge other European countries' involvement in slavery

and the lack of industrialisation that states like France achieved.

Comparative analysis of Dutch and British experiences of imperial

development via commercial expansion is the subject of David

Ormrod's The Rise

of Commercial Empires (CUP, 2003); in his review, Pieter

Emmer broadly agrees with Ormrod's thesis that 'Britain seized

the imperial initiative by centralizing its economic and governmental

institutions at home and by decentralizing its commerce abroad',

while suggesting further examples of how the Dutch commerce

in the West Indies failed to be as dynamic as British ventures.

Experiencing empire

Just as economic histories of empire are increasingly

looking more comparatively and critically at the ways in which

colonisation and imperial governments were funded and managed,

so social and cultural historians have developed new routes

into exploring experiences of empire, of colonisers and colonised

- through studying contemporary media, cultural imports and

exports, gender, education and more. Disease and medicine is

one such route. Michael Worboys is intrigued by Sheldon Watts'

approach in his Epidemics

and History: Disease, Power and Imperialism (Yale UP, 1997),

which investigates the

'role of imperialism in creating the conditions in which major

epidemics developed, and the weak responses that colonial governments

made to these problems', across continents and chronology,

while Watts feels that Worboys' comments show an insufficient

appreciation of 'the extent of the cultural impact (to say

nothing of the disease impact on non-immunes) which even a

few well-armed colonialists could make on an indigenous culture.'

More positively, Mark Harrison's review of Jane Buckingham's

study, Leprosy

in Colonial South India: Medicine and Confinement (Palgrave,

2002) , concludes that such a topic can provide 'many useful

insights into the broader social and political dynamics of

imperialism', by demonstrating 'the growing sense that disease

was an imperial problem, rather than merely a local one'.

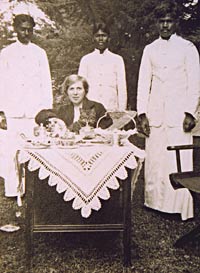

Another growth area for imperial history is gender. As Clare

Midgeley notes in her review of Julia Bush's

Edwardian Ladies and Imperial Power (Leicester UP, 2000),

gendered responses to empire were crucial to harness, at a

time when 'leading imperialists of the period were increasingly

turning their attention away from military conquest - the province

of men - towards building a settled, civilising Empire - a

project to which women were seen as vital'. And such approaches

are also important for the wider field of gender history: as

Julia Bush stresses in her response,

the predominant support for empire amongst upper-class women

and 'their refusal to fit comfortably within the established

paradigms of modern feminist history is a challenge to those

paradigms themselves'.

Yet there is some concern among historians that the perspectives

from which imperial experiences are drawn are becoming too

clearly set as opposites: the oppressors and the oppressed,

or the supporters and opponents. As Peter Marshall writes in

his review of David Cannadine's Ornamentalism:

How the British Saw their Empire (Allen Lane, 2001), 'Historians

have written a great deal about imperial enthusiasts ... and

a fair amount about the opponents of empire. They rarely write

about the great mass who were neither enthusiasts nor critics,

but 'went along'.

Colonial decline and decolonisation

With the dismantling of empires - whether Roman,

Mughal or Soviet - comes the need to study how and why such

break-ups occur, as well as critical attention to what happens

after imperial administrations have ceased to function. The

consequences of British imperial decline and decolonisation

in the middle of the last century are debated in Frank Heinlein's

book, British Government

Policy and Decolonisation 1945-1963 (Frank Cass, 2002),

in particular the management of what is termed 'informal empire'.

Its reviewer, John Kent, commends Heinlein for his 'perceptive

analysis of why the formal empire was abandoned' in favour

of a more informal network of influence: 'the appearance of

this influence was perceived as desirable by British policy

makers in ways which reflected something more than power measured

in military or economic strength.' Heinlein, in his response

to Kent, critiques the latter's use of terms like 'loss' and

'abandonment' in discussing British decolonisation, arguing

that the central tenet of his book is to show how this informal

empire survived upto and beyond the end of the period under

study, 'albeit in a strongly reduced form'.

A resurgence in nationalism is perceived as a natural corollary

to 'the movement away from dreams of imperial self-sufficiency'

(William Gervase Clarence Smith); at the same time as there

has been, in Europe at least, a movement towards greater federation

of, and cooperation between states. As Geoffrey Hosking notes

in his response

to Peter Gatrell's review of Russia: People and Empire 1552-1917

(Harper Collins, 1997), it is geography that has in part wrought

this change: for post-Soviet Russia 'There is no major geo-strategic

threat ..., such as requires it to remain an empire, still

less to try to recreate a former empire.' Perhaps it is geography

- human, political and economic - as much as trade, culture

and religion, which will shape historical approaches to empire

in the early twenty-first century, a factor which will surely

mean that the traditional identification of imperial history

with British history alone, will be left far behind.

|

| Foreword:

British Imperial History 'New' And

'Old'

In the

1970s it was commonplace to assume that the study of

British imperial history, like the British empire itself,

was on its last legs. Students, it was supposed, no longer

wished to study an irrelevant past; they were concerned

now not with vanished empires but with the history of

the peoples who had attained independence and for whom

the imperial experience had been a transitory interlude.

The situation at the end of the twentieth century is

very different. British imperial history is in apparently

robust health, widely studied in one form or another

in schools and in higher education.

In 1999 the North American Conference on British Studies

issued a report on ‘The State and Future of British

Studies’ in the United States and Canada. In general,

this report sounded an anxious note about the decline

in the study of British history. The history of the British

empire was, however, seen as an exception, where interest

was still running at a high level. In an uncertain world

for would-be academics on both sides of the Atlantic,

there seem to be clear indications that university departments

feel a need to employ historians of the British empire.

In Britain at least, it is posts in the pre-colonial

history of territories once incorporated into the empire

that now sadly go unfilled. British people of a certain

age and intellectual disposition tend to bewail the ignorance

of British school children of the British imperial past

about which they are said never to be taught. Such lamentations

are not well founded. The National Curriculum allows

provision for the study of imperial history at a number

of levels and the subject appears to be widely taught.

Far from being seen as dated and irrelevant, the history

of empire now seems to be intensely relevant not only

for understanding the historical evolution and present

state of countries once subjected to British imperial

rule but to the understanding of Britain itself. There

are many reasons why this might be so. The increasing

ethnic diversity of British society, the interest of

so many British people in family history that often involves

an imperial connection, the apparent similarities between

a contemporary global economic order underpinned by American

power and the role once played by Britain or the disillusionment

with the nation states that emerged from colonial rule

now felt by many Asian and African intellectuals –

all encourage the study of Britain’s imperial past.

A self-consciously ‘new’ imperial historiography

has contributed much to the present vitality of the subject,

proving extremely attractive to students in higher education.

Boundaries between ‘old’ and ‘new’

interpretations of a subject are usually somewhat nebulous,

existing largely in the eyes of their practitioners.

So it is with imperial history. Nevertheless, in crude

terms, the concerns of imperial history can be said to

have traditionally focused on political or economic domination:

that is, on the one hand, on military force, civil administration

and systems of rule and the eventual transfer of power,

and, on the other, on economic development or ‘exploitation’,

the special concern of a powerful Marxist tradition of

writing about imperialism. Cultural issues, such as education,

religious change or language policies, have also long

been the staples of imperial history. Indeed, Professor

John MacKenzie, who, through his own writing and the

Manchester University Press series 'Studies in Imperialism'

of which he is editor, has done so much to stimulate

the cultural history of modern British imperialism, has

distanced himself from the canonical works of the ‘new’

imperial history. Cultural history is, however, the defining

concern of the new historians. For them, political and

economic domination are assumed, but what interests them

is cultural domination, which they see as having had

a decisive effect both on the ruled and their rulers.

They start with the unexceptionable proposition that

domination involves more than physical or economic coercion;

it exists in the minds of the dominated and those who

dominate them. Obvious systems of domination are the

ordering of the world into hierarchies based on assumptions

about ‘higher’ and ‘lower’ races,

separated by immutable physiological differences, or

about stages of human progress, some peoples having attained

‘civilisation’ while others remain sunk in

‘barbarism’ or ‘savagery’, from

which they will only escape by outside intervention.

Such assumptions confirmed the rulers in their sense

of superiority and in their mission to bring about change,

while convincing, it was hoped, the ruled of their place

in the scheme of things.

The new imperial history, however, goes far beyond these

overt systems of mental domination. An imperial presence

is revealed in central works of the English literary

canon, such as Mansfield Park or Jane Eyre. Virtually

all claims to knowledge about the non-western world and

all attempts to ‘represent’ its peoples in

descriptive writing or in any form of art are exercises

of power and are assumed to be tainted by imperial assumptions.

Underlying such arguments is a rejection of claims to

knowledge that purport to reveal an objective reality.

Such claims constitute no more than the prevailing ‘discourses’

about a subject, which ultimately reflect the dominant

power in society. The mapping of colonial territories,

the writing of the history of their peoples or the collection

information about them through ethnographical or anthropological

researches – all were (and for many critics still

are) exercises of power.

Imperial ways of envisaging the world are thought to

have had a profound effect both on its colonies and on

Britain itself. Colonial elites of course rejected those

aspects of British thought that overtly consigned them

to inferiority. But they willingly imbibed its underlying

assumptions. British political and cultural norms became

their political and cultural norms. They suppressed their

own traditions or, more commonly, adopted distorted versions

of them, derived from British teaching. Their nationalism,

with its objective of a nation state, demonstrated the

intellectual thrall in which they were still held. Identities

are a prime concern of the new imperial history, which

sees nations not as primordial entities existing from

remote ages, but as imagined constructions, constantly

being reimagined with shifts of power. The colonial past

enabled the elites of new nations to define themselves,

but the imperial experience also defined Britain. The

British sense of themselves as a people came to depend

on the exercise of imperial power over others, whose

deficiencies highlighted Britain’s national virtues.

Empire, for instance, helped to shape British ideals

of masculine and feminine roles. With some justice, historians

of Britain are often accused of insularity in either

ignoring Britain’s imperial involvement or keeping

it segregated as a separate topic. For the new imperial

historians, British history without the empire makes

no sense at all.

New imperial historians are concerned not only with exposing

the all-pervasive influence of empire throughout the

world, but also put forward a programme for countering

that influence. The historian should not be content with

seeing the past through the eyes of the dominant elites,

but must try to recover the points of view of those suppressed

by imperial systems and their heirs, that is of ‘subaltern’

groups of the poor and dispossessed and of women. The

ultimate implication is that those who understand the

dead hand of the imperial legacy that has outlived the

empire in their own countries will be able to free themselves

from it, just as the British can free themselves of the

racism and chauvinistic nationalism they adopted with

empire.

It is not difficult to see why an intellectually ambitious

approach to the past, with obvious relevance to present

discontents, has proved so attractive. Yet those who

cannot accept its suppositions and who perforce are left

as practitioners of an ‘old’ imperial history

need not feel antagonistic to it. Still less need they

fear that it will make them redundant, unless it can

be countered. They should rather welcome the stimulus

that the new imperial history has given to the study

of the British empire, while also recognising that huge

areas of their subject remain largely outside its concerns;

and that within its chosen ground of cultural history

there is room for constructive disagreement and debate.

The military, political and above all the economic history

of the British empire cannot of course be taken as simply

the given background to cultural history. They are of

perennial interest in themselves and require constant

reassessment. Although the new imperial history, with

its scepticism about what can be known of the ‘real’

world, seems to have difficulty in engaging with economic

history, a discipline pre-eminently concerned with concrete

knowledge, imperial history without an economic dimension

is a very poor thing. Studies that draw on the new imperial

history have, for instance, convincingly demonstrated

connections between British medical doctrine about ‘tropical’

diseases and other assertions of imperial authority.

Nevertheless, the medical history of the British empire

is much more than the analysis of discourse. It has to

explain the inescapable reality of mass mortality in

the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

On the cultural history of empire, historians who are

outside the pale of the ‘new’ have much to

learn from those within it, especially a proficiency

in the close reading and interpretation of texts. They

can also welcome recent developments that have moved

on beyond the analysis of colonial knowledge, as in Edward

Said’s seminal Orientalism (London: Routledge and

Kegan Paul, 1978), as purely a construct of western dominance,

towards a view that accepts that the ruled as well as

the rulers took parts in producing a ‘hybrid’

knowledge of western and indigenous constructions. The

British in India did not, for instance, invent caste,

but put their own interpretations on existing doctrines

and practices.

There is, however, still room for disagreements. These

are mostly likely to arise from ‘old’ historians’

concern for context. However ingenious or convincing

the interpretation offered in ‘new’ studies

of particular texts or case studies, they seem on occasions

to be used to support generalisations that cannot easily

be sustained. The debate about empire and changing national

identity in Britain is, for example, still open for that

reason. Studies of individuals or even of localities

have revealed a high degree of awareness and commitment,

but they have to be set against other evidence of mass

ignorance or indifference. The subject as a whole can,

however, only gain from such debates. There seems to

be abundant room for both new and old within the spacious

mansion of a vibrant imperial history.

Professor Peter J. Marshall,

CBE, FBA, Rhodes Professor of Imperial History Emeritus,

King's College London. |

Back to top

|

British Empire & Commonwealth

Museum

Imperialism

and empire are words suddenly in vogue again. There

is a burgeoning of courses on empire and colonial studies

in the UK as well as in the US. In 1990 there was an

annual number of 47 historical publications relating

to empire. This had increased to 164 by 2000, and to

over 1000 by 2003 reflecting the changing political

climate as well as the general increase in history-related

publishing.

This growing interest has been

fuelled by media exposure, notably Niall Ferguson's

Empire TV series and book. Following the Prince of

Wales 2003 summer school, calling to reinstate Britain's

imperial past at the core secondary school curriculum,

an article cited a teacher's opinion that 'tales from

the imperial past would mean nothing to the many Balkan

refugee children she teaches' (Nicholas Pyke,

The Guardian, 5 July 2003).

I would endorse the call for

the return of empire as part of the history curriculum,

but more importantly, would urge all educators to consider

contextualising their teaching and seek relevant links

between the past and the present. The past did not

happen as a series of disconnected events that have

somehow stopped to make way for the present, even though

the way the National Curriculum is taught may make

it seem that way. It is dispiriting that teachers (hopefully

a minority) do not see the general relevance and issues

raised in a 500-year period that was so globally significant,

affecting a quarter of the world's surface and people.

Perhaps it is not a lack of vision, but a continuing

unease with the issues raised by the imperial legacy?

Embarrassment aside, it is a surprising lack of insight

not to recognize some of the patterns of the past resonating

in today's Pax Americana and in global issues of the

displacement of people and asylum seekers. There is

also a startling failure (fuelled, I believe, by ignorance)

to understand the legacy of the British empire reflected

in the multi-cultural Britain in which we live today

and to which refugees continue to come to be assimilated

. or not. Both historians and our museum visitors seem

to be further ahead in their thinking. Linda Colley

was quoted in the Times (17 August 2003), in the context

of Iraq as saying:

History has a way

of reminding you and it would have been useful if people

had thought more about the British empire in the Middle

East in the early twentieth century and how difficult

that had been before embarking on this. I think George

Bush, and indeed Tony Blair, should sit down with a

history book.

And a comment on

the visitor’s board at the museum refreshingly

states: ‘At last a museum which examines the

empire in context! This has a place in our history.

Let’s use this and learn from it.’

The history of empires (including

but not exclusively concerning the British), the control,

the conflicts and the stories of migration involved

in those histories are being mirrored throughout the

world today and I believe are particularly relevant

to refugees and asylum seekers. One of the most rewarding

things as Head of Education at the newly-opened British

Empire & Commonwealth Museum in Bristol is to see people

- from all sorts of diverse backgrounds - finding something

in the story that speaks to them. For many young people,

particularly black and other minority groups, the school

syllabus does not help them understand their own sense

of self and their heritage: 'Thanks for showing me

a part of history my school has completely ignored',

Nick L., aged 12. The museum engenders in its visitors

both an emotional response and a degree of empathy

no matter what your personal perspective:

It is the first

time I've been in a museum dealing with the subject

of equity/inequity/ethnicity and seen black people

presented with dignity (their own true voice) - particularly

older black men and women. That more than any other

aspect of the museum was very emotional for me.

(Maria, Museum visitor)

The narrative of empire provides

a framework for understanding many of the issues of

the past, as well as those that continue to confront

society today. In our active schools' programme we

do not teach empire for empire's sake. Students can

embark on one of our 'learning journeys' exploring

historical topics such as Tudor navigation, Victorian

trade, or war and the Commonwealth. They can take part

in art and textile workshops, inspired by artefacts

from India or Africa, or look at global education issues

such as poverty and fair trade. The history of empire

contextualizes so much else, and looking back to see

what happened in the past can help us make sense of

the present and look forward to the future: 'A wonderful

museum. Our future is moulded by our past and it is

so important for us all to understand where we came

from. It is up to us all to move on and create a better

world.' (Kim, Midlands)

The ongoing legacy

of empire is, of course, the multi-cultural society

in which we live, as well as our language, sport, food,

dress and of course, our politics. Unlike many museums

with a particular local or a national focus, the British

Empire & Commonwealth Museum has a genuine international

angle. It can therefore inform our understanding of

how people perceive Britain today on the world stage.

Tellingly, 58% of our visitors rank language and artistic

culture as the most significant area of difference

to preserve between cultures, compared with only 31%

believing it is religion and moral values. One example

of how shortsighted our view of our 'place in the world'

is shown by the limited awareness there is among the

general public regarding the historical basis of the

Commonwealth. It exists as a significant non-political

system for sharing education and technology, promoting

international understanding and world peace across

54 independent states. It consists of 1.7 billion people

- that is 30% of the world's population - and over

a quarter of its land surface. Another example is the

limited knowledge of the consequences of our colonial

involvement in various territories. Very few Britons,

for example, realize that Palestine is a former British

colony gained after the First World War. Britain saw

no solution to the Jewish-Arab conflict (which still

continues today) and withdrew its forces in 1948. An

oral history project on the Palestine police (drawn

from Arab, Jewish and British backgrounds) carried

out with Oxford University will help improve public

awareness of some of this history and the ongoing issues

that derive from this British involvement.

Given that the

aim of the museum is to present neither a celebratory

nor a condemnatory picture of the empire, the overwhelmingly

positive press reviews since it opened suggest some

measure of success. It has been described as 'a valuable

and accessible narrative, imaginatively and carefully

told' (Gary Younge, 'Distant voices, still lives',

The

Guardian, 2 November 2002), and 'a brilliant new

museum' (Radio 4). Linda Colley suggested in the Sunday

Telegraph (27 October 2002) that there are valuable

lessons to be learnt from exploring such a history:

We may be in a

post-colonial world but we are not yet in a post-imperial

world. This museum could illuminate how empires work:

how a small polity like Britain was able through its

economy, navy and advanced communications to sprawl

over vast stretches of the globe. America is doing

the same thing today.

With such a vast

story to tell, there is little space for celebrating

the richness of multi-racial Britain today: over 300

languages and at least 14 faiths that exist among the

population of 60 million. The Museum covers stories

of mass movements of people, from slavery, to indentured

labour, partition and the two World Wars. The current

displacement of people throughout all parts of the

world and the issues they face share much in common

with this past. The issues are controversial - racism,

economic exploitation, and cultural imperialism. But

denial does not make them go away. Britons of all races

need to know this history, to make sense of modern

society and to move confidently into the future.

Katherine Hann

Head of Education and Interpretation,

British Empire & Commonwealth Museum

Station Approach,

Temple Meads,

Bristol, BS1 6QH

Tel: 0117 925 4980

Email: admin@empiremuseum.co.uk

Website: www.empiremuseum.co.uk

[The views expressed in this article are personal to

Katherine Hann and not necessarily those of her institution.]

Back

to the top |

Empire on the Web

The

study of imperial and colonial history has a wide scope, covering

many centuries, continents, and cultures, and representation

on the Internet reflects this. The British Empire alone is

a subject with myriad routes of study and research, with the

possibility of concentrating on one facet, such as the military,

political, economic, or cultural history of the Empire. Assessment

of Britain's colonial history is also incomplete without the

consideration of the process of decolonisation, and its effects

across world history. The documentation of this very global

subject on the Internet is often disparate, although there

are several sites that view the Empire as a whole. The BBCi

web site The

British Empire is one of these, and whilst not absolutely

comprehensive it offers articles by leading historians on many

aspects of imperial history, and engaging interactive material.

The academic portal site British

Empire Studies also covers all the Empire, providing a

directory of resources and a general forum for researchers.

In addition, sites such as the British Library's Asia, Pacific

& Africa Collections

provide an excellent guide to their holdings of imperial and

colonial material, including the records of the East India

Company and the India Office.

Many sites have a far more singular focus,

concerning themselves with events in particular countries.

The Signatories of the Treaty of Waitangi site

is of this kind, documenting initial relations between the

British and the New Zealand Maori's.

In recent years there has been a movement

towards the research of the social and cultural history of

the British Empire, and the important contribution of colonial

subjects to British history. We Were There

explores the role of colonial subjects in the British Armed

Forces, and reminds that imperial history is not exclusively

about its white participants, whilst the Political Discourse: Theories of Colonialism and Postcolonialism site

is a useful reference guide to postcolonial theories, and

the cultural reaction of former colonies.

Of course, Great Britain was not the only

nation to have an empire, and despite a number of irritating

pop-ups, BoondocksNet.com is

a valuable site that reminds of the United States' own imperial

designs, and the corresponding anti-imperial movement.

Back to the

top

|